(Extracts from articles, pamphlets etc.)

The Initial Period (1921-25)

1

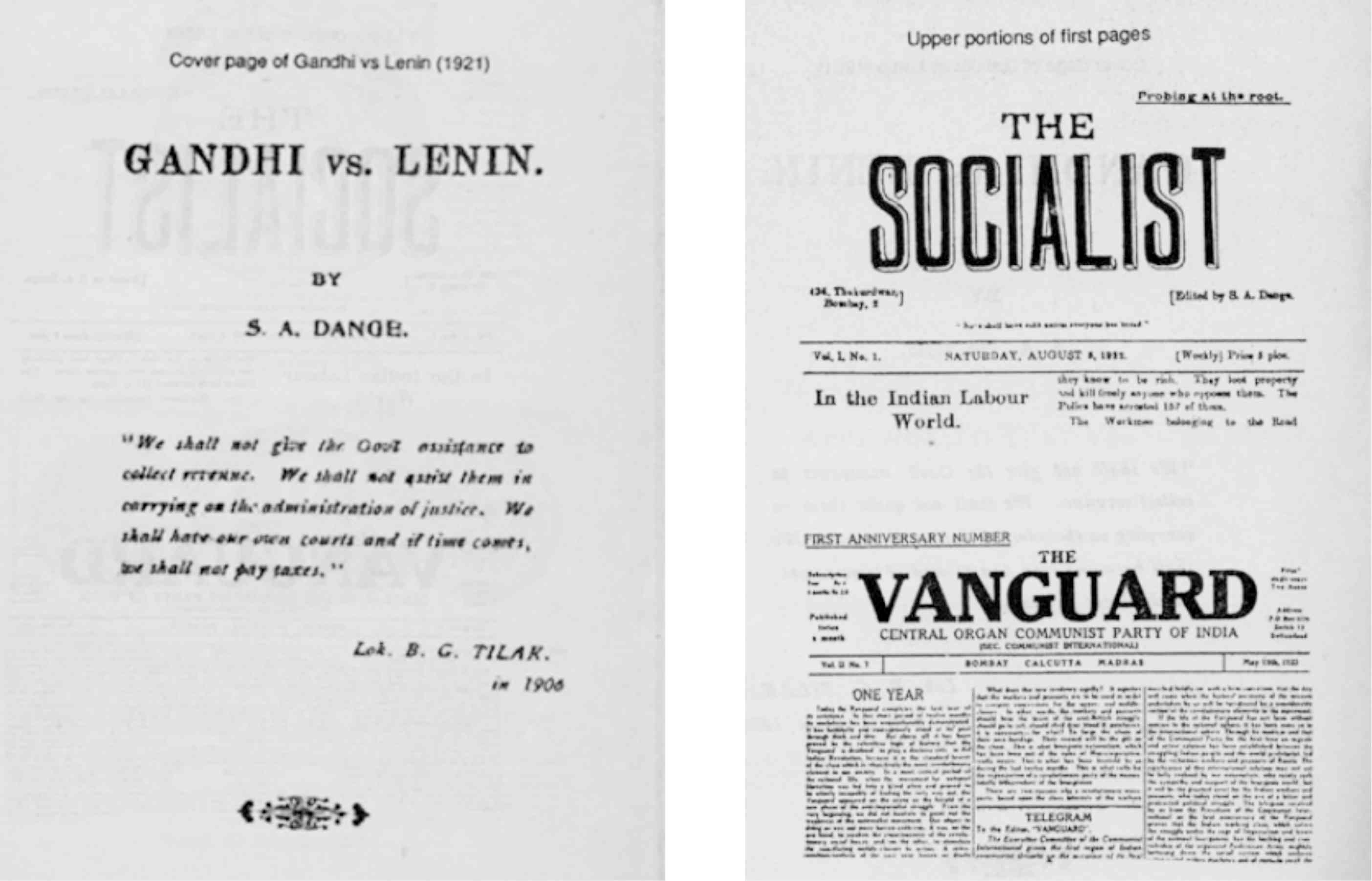

Excerpts From

Gandhi Vs. Lenin

— by SA Dange

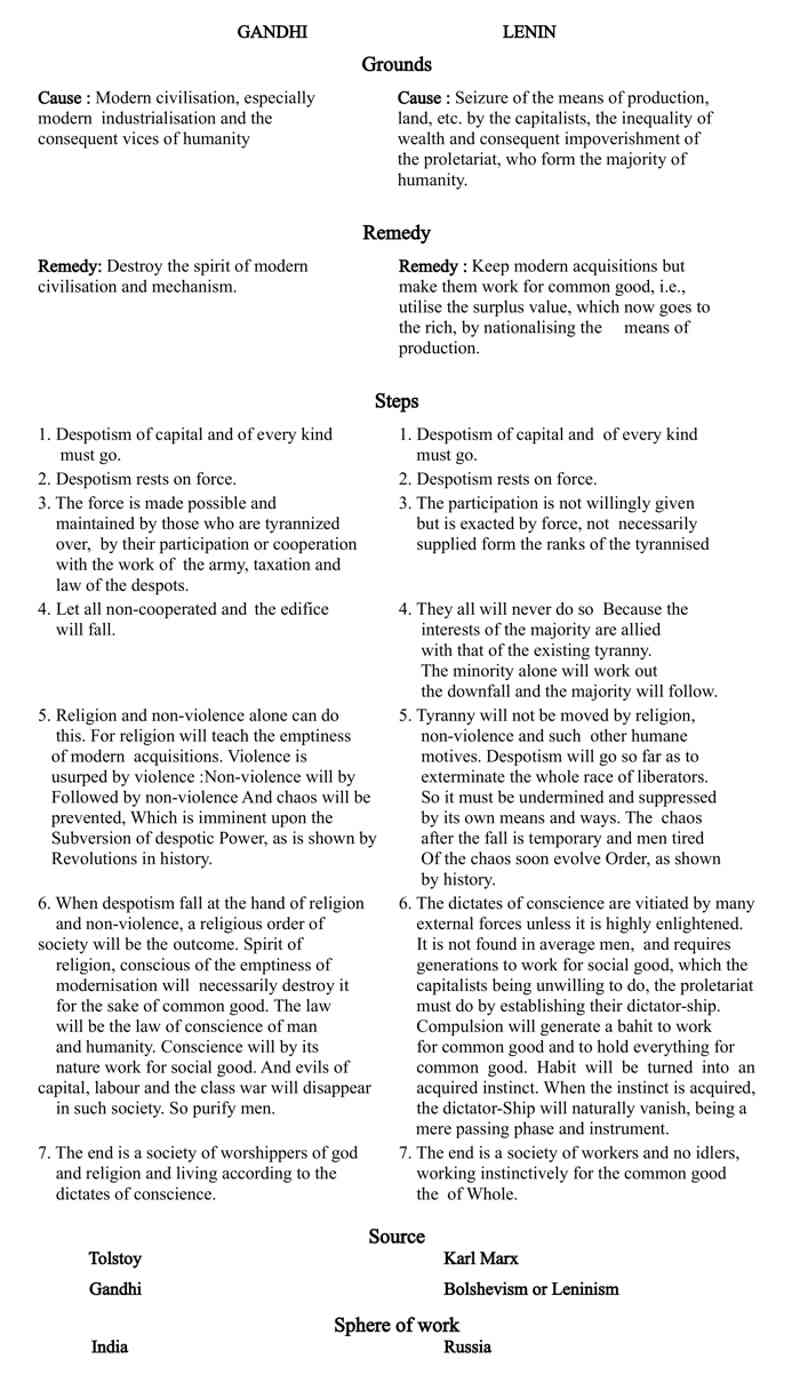

Gandhi and Lenin

Common Aim: To destroy social evils of the day, especially the misery of the poor and to subvert despotism.

Source : Chapter III of the book with the same heading

2

From

Manifesto to the 36th Indian National Congress, Ahmedabad, 1921

You have met in a very critical moment of the history of our country to decide various questions affecting gravely the future of the national life and progress. The Indian nation today stands on the eve of a great revolution, not only political, but economic and social as well. ...

This newly acquired political importance obliges the Congress to change its philosophical background, it must cease to be a subjective body, its deliberations and decisions should be determined by the objective conditions prevailing and not according to the notions, desires and prejudices of its leaders. ... The old Congress landed in political bankruptcy because it could not make the necessities of common people its own, it took for granted that its demands for administrative and fiscal reforms reflected the interests of the man in the street, ... You, leaders of the new Congress, should be careful not to make the same mistake because the same mistake will lead to the same disaster. …

[The new Congress] has discarded the old impotent tactics of securing petty reforms by means of constitutional agitation. Proudly and determinedly, the Congress has raised the standard with “Swaraj within a year” written on it. Under this banner, the people of India are invited to unite, holding this banner high you exhort them to march forward till the goal is reached. ... But the function of the Congress, as leader of the nation, is not only to point out the goal, but to lead the people step by step towards the goal. ... Several thousand of noisy, irresponsible students and a number of middle-class intellectuals followed by an ignorant mob momentarily incited by fanaticism cannot be the social basis of the political organ of a nation. The toiling masses in the cities, the dumb millions in the villages must be brought into the ranks of the movement if it is to be potential. How to realise this mass organisation is the vital problem before the Congress. ... Is it not a fact that hundreds of thousands of workers employed in the mills and factories owned by rich Indians, not a few of whom are leaders of the national movement, live in a condition unbearable and are treated in a manner revolting? Of course by prudent people such discomforting questions would be hushed in the name of the national cause. The argument of these politicians is “let us get rid of the foreign domination first”. Such cautious political acumen may be flattering to the upper classes, but the poor workers and peasants are hungry. If they are to be led on to fight, it must be for the betterment of their material condition. The slogan which will correspond to the interest of the majority of the population and consequently will electrify them with enthusiasm to fight consciously is “Land to the Peasant and Bread to the Worker”. The abstract doctrine of national self-determination leaves them passive, personal charms create enthusiasm loose and passing. ...

[The People’s] consciousness must be aroused first of all. They must know what they are fighting for. And the cause for which they fight must include their immediate needs. ... The first signs of the end of their age-long suffering should be brought within their vision. They should be helped in their economic fight. The Congress can no longer defer the formulation of a definite programme of economic and social reconstruction. The formulation of such a constructive programme advocating the redress of the immediate grievances of the suffering masses, demanding the improvement of their present miserable condition, is the principal task of the 36th Congress.

Mr. Gandhi was right in declaring that “The Congress must cease to be a debating society of talented lawyers”, but if it is to be, as he prescribes in the same breath, an organ of the “merchants and manufacturers”, no change will have been made in its character, in so far as the interests of the majority of the people are concerned. ... If the Congress makes the mistake of becoming the political apparatus of the propertied class, it must forfeit the title to the leadership of the nation. Unfailing social forces are constantly at work, they will make the workers and peasants conscious of their economic and social interests, and ere long the latter will develop their own political party which will refuse to be led astray by the upper class politicians.

Non-cooperation cannot unify the nation. If we dare to look the facts in the face, it has failed. It is bound to fail because it does not take the economic laws into consideration. The only social class in whose hand non-cooperation can prove to be a powerful weapon, that is the working class, has not only been left out of the programme, but the prophet of non-cooperation himself declared “it is dangerous to make political use of the factory workers” ...

For the defence and furtherance of the interests of the native manufacturers, the programme of swadeshi and boycott is plausible. It may succeed in harming the British capitalist government, though being based on wrong economics, the chances of its ultimate success are very problematical. Rut as a slogan for uniting the people under the banner of the Congress, the boycott is doomed to failure, because it does not correspond, nay it is positively contrary, to the economic condition of the vast majority of the population. ...

It is simply deluding oneself to think that the great ferment of popular energy expressed by the strikes in cities and agrarian riots in the country is the result of the Congress, or, better said of the non-cooperation agitation. ... The cause of this awakening, which is the only factor that has added real vigour and a show of majesty to the national struggle, is to be looked for in their age-long economic exploitation and social slavery. The mass revolt is directed against the propertied class, irrespective of nationality. This exploitation had become intense long since but the economic crisis during the war period accentuated, it. The seething discontent among the masses which broke out is open revolt on the morrow of the war was not, as the Congress would have it, because the government betrayed all its promises, but because the abnormal trade boom in the aftermath of the war intensified the economic exploitation to such an extent that the people were desperate and all bonds of patience were broken ...

What has the Congress done to lead the workers and peasants in their economic struggle? It has tried so far only to exploit the mass movement for its political ends. ... Of course it should not be forgotten that with or without the leadership of the Congress, the workers and peasants will continue their own economic and social struggle and eventually conquer what they need. They do not need so much the leadership of the Congress but the latter’s political success depends entirely on the conscious support of the masses. Let not the Congress believe that it has won the unconditional leadership of the masses without having done anything to defend their material interests.

His personal character may lead the masses to worship the Mahatmaji, strikers engaged in a struggle for securing a few pice increase of wages may shout “Mahatmaji ki jai”, the first fury of rebellion may lead them to do many things without any conceivable connection with what they are really fighting for; their newly aroused enthusiasm, choked for ages by starvation, may make them burn their last piece of loin cloth; but in their sober moments what do they ask for? It is not political autonomy nor is it the redemption of the Khilafat. It is the petty but imperative necessities of everyday life that egg them on to the fight. ... They rebel against exploitation, social and economic, it does not make any difference to them to which nationality the exploiter belongs ...

Words cannot make people fight, they have to be impelled by irresistible objective forces. The oppressed, pauperised, miserable workers and peasants are bound to fight because there is no hope left for them. The Congress must have the workers and peasants behind it, and it can win their lasting confidence only when it ceases to fight because there is no hope left for them. The Congress must have the workers and peasants behind it, and it can win their lasting confidence only when it ceases to sacrifice them ostensibly for a higher cause, namely the so-called national interest but really for the material prosperity of the merchants and manufacturers. If the Congress would lead the revolution which is shaking India to the very foundation, let it not put its faith in mere demonstrations and temporary wild enthusiasm. Let it make the immediate demands of the trade unions, as summarised by the Cawnpore workers, its own demands, let it make the programme of the kisan sabhas its own programme, and the time will soon come when the Congress will not stop before any obstacle, it will not have to lament that swaraj cannot be declared on a fixed date because the people have not made enough sacrifice. It will be backed by irresistible strength of the entire people consciously fighting for their material interest. ...

While the Congress under the banner of noncooperation has been dissipating the revolutionary forces, a counter- revolutionary element has appeared in the field to misled the latter. Look out! The revolutionary zeal of-the workers is subsiding, as shown by the slackening of the strike movement, the trade unions are falling in the hands of reformists, adventurers and government agents, the aman sabhas are captivating the attention of the poor peasants by administering to their immediate grievances. The government knows where lies the strength of the movement, it is trying to divorce the masses from the Congress. ... The consciousness of the masses must be awakened; that is the only way of keeping them steady in the fight.

Fellow countrymen, a few words about Hindu-Moslem unity which has been given such a prominent place in the Congress programme. The people of India are divided by vertical lines, into innumerable sects, religions, creeds and castes. To seek to cement these cleavages by artificial and sentimental propaganda is a hopeless task. But fortunately, and perhaps to the great discomfiture of the orthodox-. patriots, who believe that India is a special creation of providence, there is one mighty force that spontaneously divides all these innumerable sections horizontally into two homogeneous parts. This is the economic force, the exploitation of the disinherited by the propertied class. This force is in operation in India, and is effacing the innumerable vertical lines of social cleavage, while divorcing the two great classes further apart. The inexorable working of this force is drawing the Hindu workers and peasants closer and closer to their Moslem comrades. This is the only agency of Hindu-Moslem unity... it is being realised practically by the development of economic forces.

Fellow countrymen, let the Congress reflect the needs of the nation and not the ambition of a small class. Let the Congress cease to engage in, political gambling and vibrate in response to the social forces developing in the country. Let it prove by deeds that it wants to end foreign exploitation not to secure the monopoly to the native propertied class, but to liberate the Indian people from all exploitation — political, economic and social. Let it show that it really represents the people and can lead them in their struggle in every stage of it. Then the Congress will secure the leadership of the nation, and swaraj will be won, not on a particular day selected according to the caprice of some individuals, but by the conscious and concerted action of the masses.

MANABENDRA NATH ROY

ABANIMUKHERJI

1 December 1921

Source: One year of Noncooperation, Chapter I.

3

From

The Indian Trade Union Congress

- MN ROY

“One of the most interesting features of the Congress was that the same Mineowners’ Association which asked the government to break up the Congress ended by requesting a hearing before the assembly of the organised workers. Permission to speak before the Congress was granted to the president of the association who declared the intention of reducing the working week to 44 hours, and invited the representatives of the striking miners to open immediate negotiations. Promises were made in the name of the owners that decent houses would be built and schools provided for the workers’ children. Still more, a deputation from the owners publicly apologised for having attempted to suppress the Congress and presented a resolution condemning their own action. This incident shows the strength acquired by the organised workers of India in the short period of their activity.”

Finally it mentions that “Two resolutions were unanimously passed: one appeals to the workers of the world to secure peace and bread for Russia” and the second declaring that “wars can be avoided only by the united efforts of the working class of the world”. ...

Source: Inprecor, Vol. II, No.l, 3 January, 1922.

4

From

The Revolt of Labour In India

— Shramendra Karsan[1]

“It is a happy augury for India that labourers are taking a leading part in the political movement. For it is they who will make India free. Mahatma Gandhi, ‘professor of pacifistology, has been able to become the leading figure in India today due to the masses’ confidence in him. The moment he betrays them in the attainment of their political-economic and social aspirations he will at once lose his influence over them. Beneath the political agitation is concealed the weapon of labour, which will be used at the opportune moment for the emancipation of the masses.

“The study of Indian labour problems then suggests that if the principal object of the labour movements in the world today be collective bargaining with the capitalists then their only recourse is a ‘mollycoddling’ method to force arbitration. But if labour is conscious of the fact that it produces all wealth and it should dictate the methods of distribution, then there can be no other way to establish the principle but the seizure of the control of the government. The government in such cases will undoubtedly be controlled by the majority which is the labouring masses. That is what the revolt of labour in India means. This is its positive, real and full meaning. And as the cause of labour is one, its International significance is quite evident.”

Source: Inprecor, Vol. II, No. 12,14 February, 1922

Note:

1. Most probably this was a pseudonym of MN Roy.

5

From

“The Awakening of India”

— By Evelyn Roy

... the arrest of Gandhi marks a temporary setback to the progress of the revolution in India. However badly, he has steered the unwieldy mass of Indian energy and opinion into one broad channel of ceaseless agitation against the existing system during the last two years. If his leadership was confused, it was because the movement itself was a chaos which bred confusion; though he has made blunders of first magnitude, he at the same time groped a way for the people out of the blind alley of political stagnation and government repression into the roaring tide of a national upheaval. The Indian movement is ready for a new leader because it is becoming every day more clarified, its inherent contradictions are becoming palpable even to its component parts, but this very clarification spells disintegration, unless some new leaders are hurled into the breach ...

May there soon arise from the ranks of Indian labour, or from the intellectual proletariat at war with foreign rule, a class conscious Gandhi who will crystallise the political confusion that reigns in the Indian movement by formulating a clear and definite programme based upon the needs and aspirations of the overwhelming majority of the Indian people by boldly raising the standard of the working class, and by declaring that only through the energy and lives of the Indian proletariat and peasantry can swaraj ever be attained.

Source: Inprecor, Vol. II, No. 32-33,5 May 1922.

6

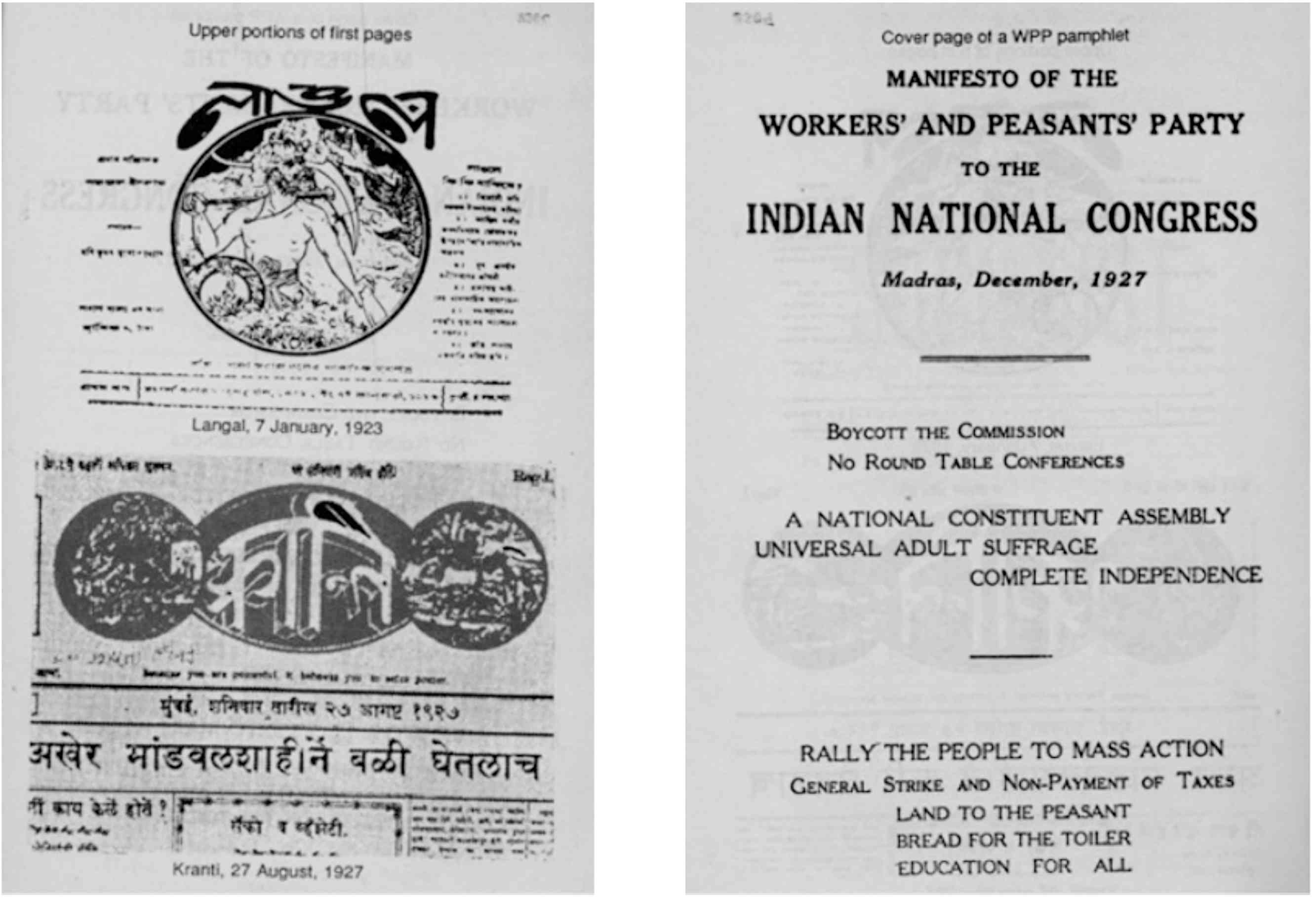

Extracts from the Editorial of The Vanguard,

vol. 1, no. 1, 15 May 1922

Our Object

... The Indian movement, like all other political movements in history, is the expression of the urge for social progress. It is a revolt of the oppressed against all that has kept them in subjugation and stagnation. ...

It is a mistake to think that the movement is the creation of great personalities. On the contrary, leaders are created by the movement. The greatness of the leader comes in where he can understand the forces behind him and can guide the movement in accordance with the natural trend of these forces. The compromising politics of the moderates, those venerable fathers of Indian nationalism, brought the extremists, who under the leadership of Gandhi assumed the title of non-cooperators, into power. But the outstanding leaders of the non-cooperation movement have so far failed to appreciate the real magnitude of the forces they are called upon to marshal on the arena of national struggle. Believers in the false philosophy which teaches that a few great men can shape the destinies of a nation, these leaders neglected to look deep into the causes which brought about the gigantic popular upheaval. They failed to understand the forces which infused fighting spirit in the hitherto inert masses. Instead of leading the rebellious masses in accordance with their immediate demands, these leaders sought to impose on them their own will and idiosyncrasies. ...

However, the movement cannot always be either betrayed by the moderates or misled by the visionary non-cooperators. The masses, who are the backbone of the struggle for national liberation, are learning to find their own way. Bitter experience gained in hard struggles is clarifying their vision ... we are entering a new phase in our struggle for freedom. We will no longer grope in the dark. We will no longer exhort the hungry people to suffer for some visionary swaraj to be attained by “soul-force” purified in the fire of poverty. Although it will be stupid to talk of premature violence, we are, nevertheless, of the opinion that non-violent revolution is an impossibility. The Indian masses — the workers organised in trade unions, the peasants forming their own fighting organs in the form of the Akali Dal, kisan sabhas, aikya sabhas etc. — call for a realist orientation in our political struggle. To help the formation of this much-needed realist orientation is the object of THE VANGUARD.

7

Extracts From An Article In Vanguard, 75 May 1922

Mr. Gandhi: An Analysis — I

— by Santi Devi

And so, Mahatma Gandhi, variously described as “the greatest apostle of non-violence since the days of Buddha and Jesus”, “the prophet of spiritualised democracy”, and “the greatest man of the world”, is in jail, condemned to six year’s incarceration by the very judge who in passing sentence paid tribute to him as “a great patriot and a great leader, and even those who differed from you in politics look up to you as a man of high ideals and a leading noble and even saintly like”. ...

... it [the present article — Ed.) is aimed to estimate as carefully and impartially as may be the essential qualities of Gandhi the saint, philosopher, politician and patriot as applied to present-day Indian conditions and to derive what valuable lessons we may from his failures as well as successes of the past three years.

Gandhi The Saint

No one can know of the life and personality of Mr. Gandhi and fail to render tribute to him as “a saintly man who purifies us at sight”. ...

... Six years’ simple imprisonment, “with everything possible to make him comfortable”, is the utmost they [the British imperialists] dare attempt, and this merely to remove him from the arena of active politics. When the storm dies down a little, they will let him free. For they will soon learn, if they do not already know, that Gandhi the saint in prison becomes to India's adoring millions Gandhi the martyr. ... It is well and truly said that, “Mahatma in jail is more powerful than Mahatma free”, not alone for the constant impetus it gives to Indian nationalism by working upon the sympathetic indignation of the masses, but because in jail his qualities of sainthood can radiate at their fullest and best uncongested by the exercise of those more worldly faculties of political leadership in which Mr. Gandhi is not so conspicuously successful.

Gandhi the Philosopher

As a philosopher, Mr. Gandhi is neither original nor unique. He merely reiterates, in an age peculiarly out of tune with his teachings, the ancient doctrine of Hinduism whose ramifications are spread through the world and which are spread at various times to inspire the prophets and saints of other lands. ...

... Is it because Mr. Gandhi sees his people disarmed and bleeding, helpless and hopeless before the superior might of the conqueror, that he counsels the philosophy of non-violence with is after all a philosophy of despair when by analysis it is patent that no one believes in its ultimate fulfilment ? For thousands of years the Indian people have listened to such counsels; for thousands of years they have heeded them, bowing their broken lives before the inscrutable working of providence, accepting their earthly lot without complaint and looking to death willingly for their deliverance. Non-violence, resignation, perfect love and the release from the pain of living — this is the substance of Indian philosophy handed down through the ages by a powerful caste of kings, priests and philosophers who found it good to keep the people in subjection. Mr. Gandhi is nothing but the heir of this long line of ghostly ancestors — he is the perfect product of heredity and environment. His philosophy of satyagraha is the inevitable fruit of the spiritual forebears. What is unfortunate is that Mr. Gandhi’s revived philosophy of other-worldliness coincides with a most unprecedented growth in Indian national life — the growth of a spirit of revolt against material privation on the part of the Indian masses. His time-honoured doctrines of orthodox Hinduism have conflicted with this news spirit of rebellion, have temporarily controlled and arrested its development, thanks to his saintly personality, which has more hold on the imagination of the Indian people than his outworn doctrines of self-annihilation. For this involuntary service, the British government has every reason to be grateful to him and it was a dim realisation of his pacific influence upon the unruly masses as well as a very wholesome fear of rousing the fury of the people to the breaking point, that made the government stay its hand so long before arresting him. It was only when Mr. Gandhi had himself prepared the way to his own arrest by schooling the masses to calmness and had stemmed the flood tide of the spontaneous upheaval of social and economic emancipation by rebuking every outbreak of mass energy, every manifestation of force on the part of the people, and by throwing the entire weight of his loved personality on the side of peace, non-violence and non-resistance that the bureaucracy dared to arrest him. The story of his political career is best studied in a separate chapter which we will title “Gandhi, the Politician and Patriot”.

Extracts from an article in Vanguard, 15 June 1922

Mr. Gandhi: An Analysis — II

— By Santi Devi

Mr. Gandhi is in jail, but Gandhism as a force in Indian politics lives on, influencing the course of the movement for good or ill ... A careful survey of his speeches and writings, as well as of his programme and tactics is enough to convince anyone that his personal and political life are merely an application of his philosophical doctrines of soul-force, self-abnegation and non-violence — of the ultimate triumph of spirit over matter. The result has been to create as the dominating force in Indian nationalism for the past three years, what has cleverly been dubbed “transcendental politics”...

Gandhi as a politician

“Swaraj by non-violence must be a progressively peaceful revolution such that the transference of power from a closed corporation to the people’s representatives will be as natural as the dropping of a fully-ripe fruit from a well nurtured tree. I say again, that such a thing will be quite impossible of attainment but I know that nothing less is the implication of non-violence” (MK Gandhi).

Here is Mr. Gandhi’s political philosophy in a nutshell. On reading it one is tempted to enquire in what way does this differ from the conception of sincere British imperialist, who openly declares the civilising mission to be to fit the Indian people for self-government by an evolutionary process of gradual, progressive stages. ... There is no contrast between his and Mr. Gandhi’s professed mode and the means to attain it. To find a contrast we must turn to the histories of past revolutions, which were made not by love and peace but by blood and iron. The English revolution of 1640; the French revolutions of 1789, of 1848 and 1870; the German, Italian and Hungarian revolutions of 1848; the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917, to cite only a few of the great liberation movements of modern times. Was there ever a revolution in the history of the world which was not ushered by force? Gandhism would learn something by a study of the past. But no, it declares, “India is a special creation of providence, she has a spiritual heritage to transmit to the world; she has evolved a spiritual civilisation like to none ever witnessed ...”

... while India’s starving millions are rioting, striking, looting and killing — in a word, behaving exactly like other normal people under the stress of hunger, overwork and privations — the burden of proof as to India’s spiritual heritage rests upon Indians themselves. ... We venture to suggest that India's spirituality is merely the remnant of medievalism clinging to the new organism about to be ushered into being as Indian nationhood. And in this connection we can but quote the profound saying of Marx — “Force is the midwife of revolutions.”

So much for the philosophy — Now for the programme and practice of Gandhism ... what swaraj is, what kind of government it implies, what definite benefit it will confer on the various classes of the Indian people, remains a vague undecided uncertainty. We know what swaraj is not only since the Ahmedabad Congress of December 1921, full three years after the movement was under way, swaraj is not “outside the British empire”, as the rejection of Hasrat Mohani's resolution definitely snowed. Swaraj is therefore some form of dominion home rule, as Mr. Gandhi himself reluctantly defined it, based upon “four anna franchise” — i.e., the right to vote being limited to those who had obtained the membership m the Congress Party by paying the regular dues ...

... The awakenings of both the peasants and proletariat were independent of the nationalist movement for swaraj; one was economic, the other political. But the nationalist movement, which needed the support of the masses immediately stepped into the leadership of this economic revolt; it sought to guide and control the activities of the people to enforce its own demands; it called hartals or strikes and suspended them at pleasure; announced boycott of foreign cloth and liquor shops, the universal use of the charkha and commanded the masses to obey. In return for this usurpation of a popular upheaval for economic betterment, what did the Congress give the masses? ... Did it hold up the banner of a material swaraj within the comprehension and necessities of the rebellious Indian people ?

No, on the contrary, it held before the eyes of the famished workers a fabulous “spiritual” swaraj, to be attained not by the brief, energetic and wholesome birth-pangs of a revolution but by the old, familiar method of suffering, sacrifice, nonresistance, repentance and prayer. The Indian masses, who had come to the end of their capacity to suffer and endure, must “purify” themselves and become perfectly nonviolent in thought, word and deed before the swaraj of the rishis, the swaraj of a handspinning, handweaving, beast-of-burden India would descent upon them like a boon from heaven. Swaraj will come, next week, next month, next year, when the hungry, naked Indian toilers had transcend-dentalised themselves. Mahatma Gandhi said so; Mahatma Gandhi was a great saint, a great sage, an incarnation of god himself, whom the white rulers could not harm, did not dare to touch; therefore, simple, ignorant men must trust, believe and blindly obey ...

Swaraj never came. One by one, then in dozens and hundreds, the national leaders went to jail. Every attempt at self-defence, at aggressive action by the masses met with sharp reproof from Mr. Gandhi — with worse than reproof, with public lamentations, fasting and prayer. The golden promise of swaraj was growing dimmer. The daily misery of the people grew ever worse; government repression, machine-guns and jails killed all the spontaneity and enthusiasm of the early struggle. Every chance for direct action was curbed by the mandate of the Mahatma; after Bardoli, the very non-payment of taxes that had swept the peasants with a thrill of hope, as well as all forms of aggressive mass actions were called off. The bewildered people were told to spin and pray for swaraj. Then came the final blow. The Mahatma, the divine incarnation, all wise, all powerful, was arrested by the white infidels, tried and sentenced to six years in jail. The heavens did not fall, neither the earth yawn at this blasphemy, doors of the jail remained locked upon the saviour of the people who remained peaceful, mute and unresisting, as he had bidden them, his expectation that the miracle justified their obedience. There came no miracle to reward their faith. British raj remained securely enthroned, swaraj was locked in the cell of the Mahatma. Waiting masses were told from behind the bars to “spin and pray”.

Mr. Gandhi as political leader cannot escape responsibility for the lamentable state of chaos that besets the Indian movement today. Gandhism must be held accountable for its mistakes as well as honour for its achievements. Constructive contribution of Gandhism in national movement as a whole are : (1) the use of mass action for the enforcement of political demands; (2) the building up of a nation-wide organisation such as the Congress Party; (3) the liberation of the national forces from governmental repression by the slogan of non-violence; (4) the adoption of noncooperation and civil disobedience, especially nonpayment of taxes as tactics in the struggle against foreign rule. Non-cooperation and civil disobedience, if property wielded, are powerful weapons in the hands of a disarmed people against machine-guns and bombing planes. But Mr. Gandhi has always shrunk from putting his brilliantly conceived tactics to proper use. The boycott was not an original contribution of Gandhism; it had been used in the partition of Bengal crisis in 1906, and Gandhism spoiled the possibility of its successful application by stressing homespun khaddar at the expense of mill-made swadeshi instead of encouraging Indian industrialism by every means.

The shortcomings and failures of Gandhism may be summarised succinctly. The most glaring defect was lack of an economic programme to win the interests and allegiance of the masses, and to make swaraj intelligible to them. Next, and closely related to this omission, was the obstinate and futile desire to unite all the Indian people, landlords and peasants, capitalists and proletariat, moderates and extremists, in a common struggle for an undefined goal. Oil and water cannot remain mixed; lion and the lamb do not lie side by side; each man follows his own material interests, in the fight for a spiritual swaraj. At the slightest danger to their property and profits these zamindars and mill-owners rally to the side of the government of law and order. If it was desired to change this government for the benefit of the majority of the people, it was necessary to sacrifice the interests of the handful of landlords and capitalists to the needs of the hungry stomachs and the naked bodies of the Indian workers and peasants. This the Congress never had the courage to do, and we cannot see that it had even the desire. ...

The third great defect of Gandhism was the intrusion of metaphysics into the realm of politics; the confusing of spiritual with temporal aims; ... Revolution is not a religion, neither is swaraj “a mental state”. To undermine, overthrow British imperialism is a material problem and to build up a national state in which the condition of the people will be improved is a question of economics, not metaphysics. ...

The fourth great defect of Gandhism is its reactionary economics. ... To go “back to the Vedas” back to the charkha, is to put away the progress of two thousand years and all the bright hopes of a future age when all will be free to cultivate their spiritual side because they have conquered, not run away from, the tyranny of material laws ....

The fifth grave error of Gandhism was its vacillations and inconsistencies, its lack of steady driving power towards a given goal. To declare non-cooperation with a satanic government, and then to seek compromise with its viceroy, to pronounce modern civilisation to be rotten to the core and “Parliaments are the emblem of slavery”, and at the same time to define swaraj as "home rule within the empire", to promise swaraj on a given date and then postpone it; to declare mass civil disobedience and then postpone it — these are a few of the innumerable and bewildering contradictions of Gandhism, which lost for it the confidence of the. masses and respect of all thinking people. ... Gandhism is not revolutionism, but a weak and watery reformism, which shrinks at every turn from the realities of the struggle for freedom. ...

Gandhi the Patriot

In closing what has been a dispassionate analysis of Mr. Gandhi’s influence upon the Indian movement, a heartfelt tribute must be paid to Gandhi the politician. We believe that Mr. Gandhi’s political career is inspired by a deep love for his suffering countrymen, a love nonetheless noble for having made great tactical mistakes ...

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi will live in the annals of his country as one of its saints and patriots, long after his political failures are forgotten.

8

A note appearing in The Socialist, 21 October, 1922

Fall In Union Membership

— a Comment

The Labour Gazette publishes a quarterly review of trade union activities in the Bombay Presidency. The third quarter of 1922 shows a decrease in the membership of the Bombay unions. The decrease is mainly found in the number of members of the BB & CI and GIP Railwaymen’s Unions in Bombay. The secretary of these unions states that it has been necessary to remove the names of a number of members from the rolls, as in spite of numerous reminders, subscriptions were not forthcoming,

For the cause of this we must dive even deeper. The union men cease to take interest and pay subscriptions because the union ceases to interest them. Union leaders forget that a union is a fighting weapon and not a banking institution to build up “fixed deposits” and “reserves”. Union leaders seem to be more actuated by a desire to please union men with the bank-reserves at their credit and naturally the worker comes to the conclusion with his instinctive logic that his own pocket or stomach-bank is as good as any other chosen by the secretary for the sums of his subscription money.

9

An article in the same issue of The Socialist

“Frame The Demand”

— by SA Dange

The Akali arrests have gone up over 2,500 and the Gurdwara Prabhandhak Committee deserves unstinted praise for its highly efficient organisation and conduct of the campaign. The reason for this is ascribed to many things and as usual the non-cooperator philosopher is ready with his deduction that his non-violent satyagraha has proved its superiority because the Akalis have remained non-violent and some philosophers have gone to the length of saying that it has proved successful, though the end is not in sight as yet.

However, if we excuse this hastiness of an impatient philosophy to install herself in a position of acceptance and look to the striking point in the Akalis, we shall find that the efficiency of the whole movement is due to the military discipline of the community. It is not the philosophic faith in the creed of non-violence that makes the Akali sacrifice himself so nobly. A few days back he marched with as much heroism and joy to cut the heads of his enemies on the war front. Violence or non-violence to him is the same. To him matters only word of superior command, as far as methods of fighting are concerned, for he has been bred to it. For himself he determines to fight and leaves the tactics, methods and means to the best judge. ...

But what is going to be the solution of the Akali tangle? In the hurry and confusion of the fight it is likely that the real issues, on which the struggle began, may be lost sight of and a false issue may occupy the ground leaving the source of the evil as it is. Anyone can see that the press of the country while speaking of the Akalis now is concerned mainly with the question whether government was cruel or not in the handling of the jathas, and the Congress Inquiry Committee too is engrossed in proving from thousands of witnesses that government was hard-hearted, and everything else that militarism can be accused of ...

What we mean to drive at is that the aim of the Akalis should be formulated and immediate demands outlined. The whole community should be made conscious of the aim of its fighting, which is not simple cutting of trees at Guru-ka-baug or removal of a few mahants. The evil of it is still deeper.

The Akalis are tillers of the soil, which is administered by the mahants in the interests of wheat speculators and exporters. During war time a great many Akalis were drawn off from the land. Demand for wheat in the foreign market raised the price of wheat and the Akali peasant was for a time prosperous. The high prices were so tempting that the Akali sold almost every grain, with the result that a shortage and wheat famine followed and Punjab was obliged to import wheat for consumption.

The prosperity of the war time soon faded away. The peasant became pauper as before and the return of disbanded men burdened the soil with more mouths and thus enhanced the evil; but the high rate of expropriation with which they were saddled by the mahants was not reduced. The Akalis looked for the source and found it in the mahant, who is merely the tool in the hands of higher expropriating organisations.

Simple removal of the mahant will not benefit the Akalis. It cannot free them from the high land tax, and the scourge of wheat cornering and speculation carried on by high finance like that of the Rallies. Only the freedom of the land from the high tax, common holding and equitable distribution will end the Akalis’ expropriation.

10

from

Message Of The Communist International To The Gaya Congress

To the All India National Congress, Gaya, India.

Representative of the Indian People !

The Fourth Congress of the Communist International sends to you its heartiest greetings. We are chiefly interested in the struggle of the Indians to free themselves from British domination. In this historic struggle you have the fullest sympathy and support of the revolutionary proletarian masses of the imperialist countries including Great Britain.

We communists are quite aware of the predatory nature of western imperialism, which brutally exploits the peoples of the East and has held them forcibly in a backward economic state, in order that the insatiable greed of capitalism can be satisfied. ... We are [not ?] in favour of resorting to violence if it can be helped; but for self-defence, the people of India must adopt violent means, without which the foreign domination based upon violence cannot be ended. The people of India are engaged in this great revolutionary struggle. The Communist International is wholeheartedly with them.

The economic, social and cultural progress of the Indian people demands the complete separation of India from imperialist Britain. To realise this separation is the goal of revolutionary nationalism. ...

Dislocation of world capitalist economy, coupled with the strengthening of the world revolutionary nationalist movement caused by the awakening of the expropriated masses, is forcing imperialism to change its old methods of exploitation. It endeavours to win over the cooperation of the propertied upper classes by making them concessions. From the very beginning of its history the British government found a reliable ally in the feudal landowning class, whose dissolution was prevented by obstructing the growth of higher means of production. Feudalism and its relics are the bulwarks of reaction; economic forces, that give rise to the national consciousness of the people, cannot be developed without undermining their social foundation. So the forces that are inimical to British imperialism are, at the same time, dangerous to the security of the feudal lords and modern landed aristocracy. Hence the loyalty of the latter to the foreign ruler.

The immediate economic interests of the propertied upper classes, as well as the prosperous intellectuals engaged either in liberal professions or high government offices are too closely interlinked with the established order to permit them to favour a revolutionary change. Therefore, they preach evolutionary nationalism whose programme is “self-government within the empire” to be realised gradually by peaceful and legal means.

This programme of constitutional democracy will not be opposed by the British government for ever, since it does not interfere with the final authority of imperialism. On the contrary its protagonists are the potential pillars of imperial domination. ...

The social basis of a revolutionary nationalist movement cannot be all inclusive, because economic reasons do not permit all the classes to participate in it. Only those sections of the people, therefore, whose economic interests cannot be reconciled with imperialist exploitation under any makeshift arrangement, constitute the backbone of your movement. These sections embrace the overwhelming majority of the nation, since they include the bankrupt middle classes, pauperised peasantry and the exploited workers. To the extent that these objectively revolutionary elements are led away from the influences of social reaction, and are free from vacillating and compromising leadership, tied up spiritually and materially with the feudal aristocracy and capitalist upper classes, to that extent grows the strength of the nationalist movement.

The last two years were a period of mighty revolutionary upheaval in India. The awakening of the peasantry and of the proletariat struck terror in the heart of the British. But the leadership of the National Congress failed the movement in the intensely revolutionary situation. ...

In leading the struggle for national liberation the Indian National Congress should keep the following points always in view :

- 1) that the normal development of the people cannot be assured unless imperialist domination is completely destroyed,

- 2) that no compromise with the British rulers will improve the position of the majority of the nation

- 3) that the British domination cannot be overthrown without a violent revolution, and

- 4) that the workers and peasants are alone capable of carrying the revolution to victory. ...

In conclusion we express our confidence in the ultimate success of your cause which is the destruction of British imperialism by the revolutionary might of the masses.

Let us assure you again of the support and cooperation of the advanced proletariat of the world in this historic struggle of the Indian people.

Down With British Imperialism !

Long Live The Free People Of India !

With Fraternal Greetings,

Humbert-Droz

Secretary,

Presidium of the Fourth Congress

of the Communist International.

11

From

The Programme[1]

Our movement has reached a stage when the adoption of a definite programme of national liberation as well as of action can no longer be deferred. ... The ambiguous term swaraj is open to many definitions, and in fact it has been defined in various ways according to the interests and desires of the different elements participating in our movement. ... Therefore a militant programme of action has become indispensable. ...

Programme of National Liberation

... The first and foremost objective of the national struggle is to secure the control of the national government by the elected representatives of the people. But this cannot be achieved with the sanction and benevolent protection of the imperialist overlords, ... Any measure of self-government or home rule or swaraj under the imperial hegemony of Britain will not amount to anything. Such steps are calculated only to deceive the people. ... The Congress must boldly challenge such measures and declare in unmistakable terms that its goal is nothing short of a completely independent national government based on the democratic principle of universal suf: rage.

Theory of Equal Partnership a Myth

The theory of “equal partnership in the British commonwealth” is but a gilded version of imperialism. Only the upper classes of our society can find any consolation in it, because the motive behind this theory is to secure the support of the native landowning and capitalist classes by means of economic and political concessions, allowing them a junior partnership in the exploitation of the country. Such concessions will promote the interests, though in a limited way, of the upper classes, leaving the vast majority of the people in political subjugation and economic servitude. The apostles of “peaceful and constitutional” means are nothing but accomplices of the British in keeping the Indian nation in perpetual enslavement. ...

No Change of Heart

Those preaching the doctrine of “change of heart” on the part of the British rulers fail to dissociate themselves clearly from such halfway measures. ... A determined fight which is required to conquer national independence for the Indian people is conditional upon a clearly defined programme, and only such a programme will draw the masses of the people into the national struggle as takes into consideration the vital factors affecting the lives of the people.

Therefore, the Indian National Congress declares the following to be its PROGRAMME OF NATIONAL LIBERATION AND RECONSTRUCTION :

- (1) Complete national independence, separated from all imperial connection and free from all foreign supervision

- (2) Election of the national assembly by universal suffrage. The sovereignty of the people will be vested in the national assembly which will be the supreme authority.

- (3) Establishment of the federated republic of India.

Social and Economic Programme

The principles which will guide the economic and social life of the liberated nation are as follows :

- (1) Abolition of landlordism. All large estates will be confiscated without any compensation. Ultimate proprietorship of the land will be vested in the national state. Only those actually engaged in agricultural industry will be allowed to hold land. No tax farming will be allowed.

- (2) Land rent will be reduced to a fixed minimum with the object to improving the economic condition of the cultivator. State agricultural cooperative banks will be established to provide credit to the peasant and to free him from the clutches of the moneylender and speculating trader.

- (3) State aid will be given to introduce modern methods in agriculture. Through the state cooperative banks agricultural machineries will be sold or lent to the cultivator on easy terms.

- (4) All indirect taxes will be abolished and a progressive income tax will be imposed upon incomes exceeding 500 rupees a month.

- (5) Nationalisation of public utilities. Mines, railways, telegraphs and inland waterways will be owned and operated by the state under the control of workers’ committees, not for profit, but for the use and benefit of the nation.

- (6) Modern industries will be developed with aid and under the supervision of the state.

- (7) Minimum wages in all the industries will be fixed by legislation.

- (8) Eight-hour day. Eight hours a day for five and half days a week will be fixed by law as the maximum duration of work for male adults. Special conditions will be laid down for the woman and child labour.

- (9) Employers will be obliged by law to provide for a certain standard of comfort as regards housing, working conditions, medical aid, etc. for the workers.

- (10) Protective legislation will be passed about old age, sickness and unemployment insurance in all the industries.

- (11) Labour organisations will be given a legal status and the workers’ right to strike to enforce their demands will be recognised.

- (12) Workers’ councils will be formed in all the big industries to defend the rights of labour. These councils will have the protection of the state in exercising their functions.

- (13) Profit sharing will be introduced in all big industries.

- (14) Free and compulsory education. Education for both boys and girls will be free and compulsory in the primary grades and free as far as the secondary. Technical and vocational schools will be established with state aid.

- (15) The state will be be separated from all religious creeds, and the freedom of belief and worship will be guaranteed.

- (16) Full social, economic and political rights will be enjoyed by the women.

- (17) No standing army will be maintained, but the entire people will be armed to defend the national freedom. A national militia will be organised and every citizen will be obliged to undergo a certain period of military training. ...

Analysis of Our Forces

... With the purpose of developing all the forces oppressed and exploited under the present order and to lead them in the struggle for national liberation, the Indian National Congress adopts the following

ACTION PROGRAMME :

- (1) To lead the rebellious poor peasantry in their struggle against the excesses of landlordism and high rents. This task will be accomplished by organising militant peasants’ unions which will demand : (a) abolition of feudal rights and dues; repeal of the permanent settlement and talukdari system; (b) confiscation of large estates; (c) management of the confiscated estates by councils of the cultivators; (d) reduction of land rent, irrigation tax, road cess, etc.; (e) fixed tenures; (f) no ejection; (g) abolition of indirect taxation; (h) low prices; (i) annulment of all the mortgages held by moneylenders etc.

- (2) To back the demands of the peasantry by organising countrywide mass demonstrations with the slogan of “non-payment of rent and taxes”.

- (3) To organise mass resistance against high prices, increase of railway fare, postage, salt tax and other indirect taxation.

- (4) To struggle for the recognition of labour unions and the workers' right to strike in order to enforce their demands.

- (5) To secure an eight-hour day, minimum wage and better housing for the industrial workers.

- (6) To back up these demands by mass strikes to be developed into a general strike at every available opportunity.

- (7) To support all strikes politically and financially out of the Congress fund.

- (8) To agitate for the freedom of press, platform and assembly.

- (9) To organise tenants’ strikes against high house rents in the cities.

- (10) To build up a countrywide organisation of national volunteers.

- (11) To organise strikes of the clerks and employees in the government and commercial offices for higher salaries.

- (12) To enter the councils with the object of wrecking them.

- (13) To organise mass demonstrations for the release of political prisoners. ...

December 1922

Source: One Year of Non-cooperation, Chapter X.

Note:

1. Better known as Roy’s Programme for the Indian National Congress.

12

Excerpts from an article published in Vanguard, Double Number, 15 October — 1 November, 1923

The Next Step

Now that the liquidation of the non-cooperation campaign can no longer be obscured by phrases, the question that faces those who are not in conformity with this liquidation is.: “what next ?” ...

... The revolutionary significance of the non-cooperation programme lay in the fact that its realisation demanded mass action. The programme of paralysing the government could not be realised by the efforts, however sincere and determined they might be, of the educated few, ... the determination to paralyse the government by withholding all support presupposed the necessity of eventually falling back upon ether social forces — forces that are more vital for the existence of the government and even the shortest period of non-cooperation which can seriously injure the government. These are the productive forces of society, namely, the workers and peasants. The profit that British imperialism makes out of its domination over India is not produced by the lawyers and students. Clerks contribute but little to it. The toil of the workers and peasants, who constitute more than 90 per cent of the population, goes into the accumulation of this profit. Any act that will cut into the source of this profit will weaken the position of the government.

... The refusal of the Indians to enlist in the army and that of the troops to fight will be the beginning of the end. Nearly 40 per cent of the entire revenue comes from the peasantry only in the form of direct land rent. If this source of income is disturbed the whole structure of the state will crack.

... The idea of paralysing the government by withholding popular cooperation evolved out of the objective situation which did not permit any other form of direct fight with the established order. This spontaneously evolved form of struggle was taken up by the Congress under the leadership of Gandhi whose subjective limitations, however, hedged in the revolutionary programme of non-cooperation. The wave of revolutionary mass movement, which alone could have led to the realisation of the non-cooperation programme, precipitated the clash between the objective and subjective factors that went into the making of the non-cooperation campaign. The Congress succumbed in this fatal clash. The journey towards Delhi, then the councils, the negotiation with the bureaucracy and finally compromise with imperialism was begun.

... Those revolutionary patriots who are not satisfied with the turn the Congress has taken at Delhi should not waste their time in recrimination. Their slogan should be “Forward !” ... They should invoke by all means those forces of revolution which were shunned by the Congress. The next step therefore is the organisation of a People’s Party comprising all the exploited elements of our society. Such a party alone will carry the non-cooperation to its logical consequences.

September 1923.

13

Excerpts from an article published in Vanguard, Vol.3, No. 4.

Manifesto On The Hindu-moslem Unity And Swaraj

1 October 1923

Hindu-Moslem unity has been justly regarded as the chief pillar on which the future swaraj of India is going to be built. Much enthusiasm was shown on the question and indeed good deal of work was done in the direction during the apparently triumphant march of the non-cooperation movement under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi and his lieutenants Ali brothers. Cooperation between Mahatma Gandhi as the leader on one hand and AH brothers and his followers on the other was regarded as an emblem of unity. But this union was not very desirable to many people. Some revolutionary thinkers believed that the union was artificial. A number of Hindu politicians had the opinion that the Musalmans were exploiting the Mahatma's popularity to further their pan- Islamic plans which were always looked upon by the Hindus with suspicion, while the reactionaries in the Moslem camp held this submission of the Ali brothers as the leaders of Indian Moslems (to the authority of the Mahatma) contrary to Islamic laws. How can a believer follow the lead of an unbeliever? This was the question on the lips of many a maulvi. The apparent triumphal progress of the movement however obliged these maulvis and pandits to keep their tongues in control. But as soon as the popular movement subsided and the Mahatma and his lieutenants were shut up in jails, these reactionary elements came out in the open and by their mischievous propaganda created disturbances among two communities.

The scene of Jallianwala Bagh and other bloody struggles, the Punjab, first of all became the scene of civil war between the Hindus and Musalmans. The troubles originated in this unhappy province spread to other prbvinces of India. ...

The root cause of all these troubles occurring in the country after the immediate collapse of the movement is that religion was allowed to play the chief part in the movement. It may be comparatively easy to fire politically backward people with religious fanaticism; but it is impossible, even dangerous, to base a political movement on such unreliable ground. The recent occurrences amply prove this impossibility and dangerousness. If the hostility against the British imperialism is made a religious issue, the hostility thus aroused can at any moment turn into antagonism among the two great Indian communities as they do not profess the same religion. It is precisely what happened now …

The khilafat demands constituted one of the principal planks of the non-cooperation platform. The khilafat movement however was essentially a political movement based on religious principles. The Ali brothers and other Moslem leaders succeeded in convincing Mahatma that the Khilafat problem was to Indian Moslems a question of life and death. Mahatma being himself a religious man assumed the championship of the khilafat movement, and a bargain was struck — Hindus to support the khilafat agitation and Moslems to take active part in swaraj movement and perhaps by and by give up cow-killing to spare the religious sentiments of their Hindu countrymen. This was the basis of the union. It was artificial in that it did not take into account operation of the material forces which alone could bring about a solid and durable national unity. It was built on the unreliable foundation of religious sentimentalism. The present debacle was a foregone conclusion of such an ill started movement.

Now to improve the situation those causes which had so much grave dangers should be eliminated. In this connection the announcement of Mushir Hossain Kidwai, that the khilafat committees should be dissolved and their activities transferred to the field of Indian politics, is valuable. The proposal has not been accepted by other leaders of the khilafat movement. The suggestion of Mr. Kidwai is useful in the way of improving the relations between the Hindus and Moslems. Action taken along the lines of the proposal will make for the growth of homogeneousness of the Indian national movement. The just complaint of most of the Hindu patriots that the Musalmans do not take an active part in the Indian affairs would be removed and the religious character of the movement would be replaced by a predominating political character. The Hindu Mahasabha movement which is a reaction to separate Moslem political organisations, especially the khilafat conference — would ultimately die down. ...

The Indian Moslems should take lesson from the decision of the grand national assembly of Angora which has declared the separating of the Khilafat from the sultanate, i.e. separating of the religion from politics. No protests from the ulemas of India will induce the progressive elements of the Turkish nation to change their decisions. Turkey has entered a new era of progress by separating religion from politics. The example of nationalist Turkey should help the Indian Moslems to decide in which direction their politics should go. Let them liberate themselves from the yoke of the British before they think of liberating other Musalmans of the world. This cannot be done until and unless they unite heart and soul with their countrymen, Hindu and other communities of India. ...

Have the Hindus and Moslem masses nothing in common in India? Are both of them not suffering equally under the ruthless exploitation of British imperialism? Are they not economically ruined by the British and Indian capitalists and landlords? ... The masses — the common workers and peasants — are however as a matter of fact already united by virtue of their common economic interests, only the consciousness of this union is interfered with by large doses of conflicting religious dogmas administered by interested parties. Religious propaganda is an indigenous method of exploitation of the ignorant masses by the able doctors of divinity. This they have to do in order to preserve feudal rights of the upper classes, without whose support they cannot live and prosper.

The lower-middle-class intellectuals who sincerely desire the freedom of their country should free themselves form these religious and communal disputes. ... They have to replace the religious propaganda and metaphysical abstractions by economic slogans to make the masses conscious and subsequently to lead them to the fight for national independence without which their own economic emancipation is impossible. When the cry of “land to the peasants and bread to the workers” is raised the masses whether Hindus or Moslems will rally to their standard.

The problem of national freedom cannot be solved unless a new programme is adopted and new tactics employed. ... Our work is to agitate and organise the masses on an economic programme and finally to lead them to a general strike or you may call it civil disobedience. Let us have no negotiation with the enemy on the eve of civil disobedience, let us carry the fight to the finish. The police and military recruited from poor peasants and workers, who have to sell themselves to the British in order to earn their livelihood, will ultimately be won to our side.

So let our programme be the economic emancipation of the masses, which must have the national freedom as its prerequisite.

One may think that this is a wrong method, as by doing so we will alienate the sympathies of the upper classes — our own capitalists, landlords and religious leaders. ... Some people will say that all Indian landlords and capitalists are not aiding the British, on the contrary, they are participating in the national struggle. So far so good, let us launch the fight on an economic programme in the interest of the masses, and if these landlords and capitalists still fight against the British imperialists the sincerity of their patriotism will be proved. Why sacrifice the interests of 98 per cent in order to please the remaining 2 per cent and especially when we know that no national freedom can be obtained without uniting the masses on economic grounds. If these 2 per cent are honestly fighting for the masses, they will continue to fight even if we adopt more concrete programme and more militant tactics.

The country is in a state of confusion now. The Congress is split into factions engaged in bitter recriminations on petty question. One is after council entry hoping thereby to obtain perhaps another installment of precious reforms. The other is in a hopeless bewilderment, not knowing what to do. ... The khilafat conference does not know where to go …

In order to clear off this confusion and to put a new life in the movement a party subordinating all religious and communal questions to the great politico economic question should be organised. The programme of the party should be neither going to the golden age of vedas, nor saving the empire of the khalifa but to free the Indian people from the political and economic serfdom. The party should speak to the Indian masses in terms of their daily needs — land, bread, housing, clothing etc. Its immediate goal would be to free India from the domination of England. The ultimate goal would be economic emancipation of the people, to create a society having no blood-suckers and wage slaves — a classless society. ...

THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA.

14

Excerpts from a commentary published in Labour Kisan Gazette, Vol. 1, No. 4.

Comrade Nikolai Lenin In Memoriam

31 January 1924.

Lenin, the great, has passed away and joined the choir invisible. The world, the worker's world is today poorer by the passing away of its great teacher and redeemer. ... It is the worker — the true salt of the earth — that mourns or ought to mourn for him who showed him the path of deliverance from bondage, privatian and misery. Teachers and prophets, statesmen and scientists, philosophers and metaphysicians equally great and equally learned have appeared from time to time, and tried to redeem the worker’s humanity from its age-long suffering and serfdom, but it was reserved to Nikolai Lenin to apply the only true and correct method of removing the great ills of life which the great capitalist interests of the world have brought upon the once happy human race.

It was his great master Karl Marx who found the great truth of historical materialism trodden underfoot, reviled and ridiculed by the powerful and the ignorant among mankind, but he lived long enough to see the great worker’s philosophy understood by the thoughtful and accepted as the method of ridding poverty and misery from this mundane existence. It was for the first time in the history of the world demonstrated with scientific precision and accuracy that most of the misery with which the majority of the world have become affected were due to the selfish aggrandisement of a few among the powerful over the toiling many. And he taught further that it was only by rendering the few powerless to continue the evil that the suffering workers will have to get rid of their misery, and attain to the life of knowledge, labour and ease, which today is the monopoly of a very few among mortals. Today Nikolai Lenin stands unrivalled among the sons of men who have tried to alleviate human sufferings and it is now left to the workers to follow his method. ...

The great revolution in political thought and philosophy which Nikolai Lenin brought in his own country may be destroyed, may even be swept away by the selfish nature of a few among men, but it will revive again and again and ultimately encompass the world, and finally render the life of the worker tolerable and pleasant throughout the world. To him who has done so much and who has given the worker a clear vision of his glorious realm in which every human being shall have the right to labour and to live like all his fellows, we lift up our hands in love, devotion and reverence.

15

Excerpts from an article published in The Socialist, 31 January 1924

Lenin Is Dead

The Russian revolution was an accomplished fact in 1917. For four years the capitalist press of the world was overthrowing the bolsheviks and killing Lenin. He could not be killed and they have never succeeded in killing him. Lenin is dead. We are afraid, this time, the wires have flashed a sad truth.

… … … … … … …

Lenin was introduced to the Indians by Reuter and the capitalist press as a monster who reveiled in massacres. The present writer tried, with what scanty information he could collect, at that time (April 1921) to present a faithful picture of the Russian revolution, of Marxism and the man, who was fighting for Marxism in Russia. The book Gandhi vs Lenin was meant to apprise Indians of the inherent fallacies of pacifism and the certain failure of pacifist methods in accomplishing a revolution in capitalist economy and political structure. But at that time pacifism was at its height of power in India. In 1921, we quoted the hero of pacifism thus, "We shall continue patiently to educate them (the masses) politically till we are ready for safe action. ... As soon as we feel reasonably confident of non-violence continuing among them in spite of provoking executions, we shall certainly call upon the sepoy to lay down his arms and the peasantry to suspend payment of taxes. We are hoping that the time may never have to be reached. ... But we will not flinch when the movement has come and the need has arisen.”

The time came and went. And ultra pacifism looked on and waited. When one of the greatest personalities in the world was thus experimenting with fallacies, Lenin with an unerring eye grasped the key of the Russian revolution. ...

Lenin and his followers possessed that single virtue that alone brings success in social upheavals. That single virtue was lacking in the class and the men that led the Indian movement. The highest spirit of revolution was absent in the class that led India from 1918 to 1923. ...

16

Excerpts from an article in Inprecor, Vol4, No. 19.13 March 1924.

The Abolition of The Khilafat

- MN Roy

The news of the abolition of the khilafat by the Turkish national assembly has burst upon the world as a bombshell. Ample space has been devoted to this topic in the bourgeois press of Europe. ...

Every imperialist country is weighing the event in the scale of its own interest. All are visibly disturbed, because it looks as- if the days when they all considered Turkey as legitimate prey are over. Nationalist Turkey has plunged herself into a revolution which will transform her so as to make European imperialism, which never gave up the hope of keeping her under perpetual domination, very uncomfortable.

It need not be said that the revolution of the Turkey national assembly is a great revolutionary step. ... The boldness of the step becomes evident when it is remembered that the position of Turkey has been morally fortified by the fact that 240 millions of Moslems in the surrounding countries owed her allegiance as the custodian of the holy sea. She has been looked upon as the leader of the Moslem world because of this fact. Her latest struggle for national liberation was interpreted by the Moslems in other lands as the struggle for the defence of the faith. Turkey was supposed to be defending the khilafat. So it can be easily imagined what a tremendous shock the news that the Turks hove abolished the khilafat will be to the Moslem world. Not only the present khalif who divested of temporal power only a few months ago is deposed, but the time-honoured institution itself is abolished. It is going farther than any other people has gone before. Neither the papacy of the Roman church, nor the patriarchate of the Greek church was ever abolished by any bourgeois revolution. They were only deprived of all influence over the state. ...

Turkey today sends a new message to the Moslems of other countries. Her message is that the struggle for national liberation cannot be fought within the bounds of theocratic tradition and the social institution that accompany it: that nationalism cannot be circumvented by religion. The revolutionary significance of this message is incalculable. This message has been given a graphic form in these words of Ismet Pasha : “If Constantinople is today in our hand, it is because we have fought to the death the Greeks and the khalif. If other Moslems have shown sympathy for us, this was not because we had the khalif, but because we have been strong.” The implication of these words is clear. Turkey now bids for the leadership of the Moslem world, not on the ground of a religious mission, but as a secularised state which has not only warded off foreign attack, but has successfully grappled with reaction at home. She faces the Islamic world, not in the supposed role of the defender of the khilafat, but as the grave-digger of that antiquated institution which for a long time has become the instrument of foreign imperialism.

As a matter of fact, the so-called-khilafat movement, which has been more evident in India than in any other country, becomes an anomaly in consequence of the action of nationalist Turkey. Although they somehow managed to reconcile themselves with a republican Turkey liberated from theocratic control, the Indian khilafatists will find it hard to swallow the wholesome words of Ismet Pasha. ... the revolutionary action of the Turkish nationalists is sure to rebound upon the Indian political horizon. There must be much searching of hearts among the Indian Moslems. There too the days of religious nationalism and extraterritorial patriotism must come to an end.

If the Indian Moslems still persist in their notion of a religious confederation, they will surely land in the camp of reaction and all their anti-British talk will ridicule them in the face. But the real grievance of the Moslem masses of India was not concerning the khilafat, it was not of a religious character. The grievance lies much nearer home and is essentially mundane by nature. Therefore the only way to prevent the Indian Moslems from falling into the snares of scheming reaction will be to abandon the treacherous ground of extraterritorial religious patriotism in favour of a healthy nationalism more concerned with material well-being than the spiritual salvation of the people. ...

The liberation of the premier Moslem country from the age-long traditions of religion opens up a new era in the history of the entire east as far as the Indian archipelago; this concerns particularly the Islamic people. The fond belief of the orthodox Indian nationalists, both Hindu and Musalman, that their country is immune from the so-called western civilisation is going to be shattered. In the course of normal progress the social and political institutions of every human community must be secularised. Civilisation is a stage of human progress which makes for the dissipation of ignorance upon which religion is based. It does not assume a different form at different points of the compass. The epoch-making character of the event with which the Turkish national assembly entered upon its fifth year of existence is graphically brought home by an editorial article in the official organ Ileri. The article, published the day after the memorable resolution was taken, was entitled, “Goodbye, Orient”.

17

From an item published in The Masses, 10 October 1926

The Communal Strife

The most outstanding and at the same time the most deplorable feature of the present situation in India is the communal strife. Communal riots are spreading all over the country. ...

Causes

There is a class of people whose mission is to go on adding fuel to the fire. They keep up the conflagration of internecine strife to gain some definite political and economic ends. This class consists of the following elements : (1) Parasitic class of priests who masquerade as maulanas and mahatmas and whose influence among the masses tends to decrease in proportion as the country goes more and more through the capitalist exploitation. It is to their material interest to kindle and to feed the flame of religious fanaticism. Faced with the menace of unemployment, so to say, they are creating work for themselves. (2) Reactionary politicians who lost ground during the nationalist movement of non-cooperation. (3) Unemployed intelligentia. The hitherto weak and less numerous muslim intellectuals are struggling against their powerful hindu rivals to get administrative posts in the country. (4) The petty-bourgeois elements engaged in trading business in the town and village. Here again the young muslim bourgeoisie in entering into a keen competition with their strong hindu compatriots. (5) Lumpen proletariat and goondas who are used by the police to start the affray. They are paid for it. …

The Hidden Hand

There is another agency which is interested to see that the civil war is kept going on. This is the hidden hand of imperialism. AH kinds of diplomatic and ingenious methods are used to encourage the communal strife, with a double purpose. ...

The British diplomats adapt their harangue according to the community which they wish to please at a particular time in order to enforce their “divide and rule” policy. When muslims are destined to be the “favourite wife” the British empire is represented to be the biggest muslim empire in the world as it counts millions of mussulmans under its yoke. ... The muslims who are sometimes called “virile” by flattery, are led to think that they must have special consideration in any scheme of swaraj because as predecessors of British rulers they have a “special status”. It is on the basis of the “special status” that the muslims demand a greater percentage of the seats than in proportion to their actual number. On the other hand when the muslims are “conspiring with his majesty’s enemies outside India” and it is desired to placate hindu feelings, it is discovered that the British are as pure Aryans in origin as the hindus. At the same time the bogey of pan-is-lamism with all its dangers to hinduism is made a subject of propaganda in the imperialist press. It is preached that if law and order are set at naught in India, if the Britishers are forced to withdraw, the Afghans would invade the country and would ensalve and loot the hindus with the support of the Indian muslims. ...