Part - III

THE BRIEF BUT SUCCESSFUL ERA OF

WORKERS’ AND PEASANTS’ PARTIES

(1926-early ’29)

This was the period when the post-non-cooperation lull reached its lowest and then began a turn-around to culminate in the Civil Disobedience Movement starting in 1930. And this was the period for the fledgling CPI to try and spread its tiny wings — the WPPs — across the political landscape in India,

The National Political Scene

Workers’ And Peasants’ Parties

WPP Vis-a-vis CPI

The Sixth Congress of Comintern

The Meerut Conspiracy Case

The National Political Scene

After Chauri Chaura the two streams of Congress activities — one of swarajists in legislatures and the other of constructive workers and satyagrahis mainly in villages — dragged monotonously on but the best revolutionary elements were being attracted towards the ideals of socialism, the new Soviet state and, at home, the organised working class movement with its great revolutionary potential. Some of these elements joined the red flag TU movement or the CPI, while some others took to a new higher stage of patriotic-terrorist activities. This latter trend was best represented by the HR A (Hindustan Republican Army) founded in October 1924 with activities in Punjab, UP and Bihar and Surya Sen’s revolutionary group in Bengal which conducted the famous Chittagong armoury raid in April 1930.

From the very outset the HRA, founded by Sachin Sanyal and Jogesh Chandra Chatterji in Kanpur, carried distinct marks of a new ideology. Its inaugural meeting decided to “preach social revolutionary and communistic principles”. Before long it also declared its resolve to “start labour and peasant organizations” and to work for “an organised and armed revolution.”[1] Its main initial activities, however, were raising funds through dacoities. One such incident – the famous Kakori Train hold up of August 1925 — led to the arrest of many, but newcomers like Ajoy Ghosh, a Bengali youth of Kanpur who would later became the General Secretary of CPI, took lessons from this and in co-operation with the 21 year old revolutionary intellectual Bhagat Singh of Lahore the HRA was reconstituted as HSRA in September 1921. The new “S” of course, stood for socialist, for socialism was now officially accepted as the goal.

The story of HRA-HSRA, and particularly of its leading spirit Bhagat Singh, is a story of an incomplete transition from petty bourgeois revolutionism to communist revolutionary mass action. The young Bhagat (born 1907) combined in himself a great patriotic zeal for revolutionary action, particularly mass action (that was why he became a founder member and first Secretary of the Naujawan Bharat Sabha (NBS) in Punjab in 1926) with a great interest in revolutionary theory. A rationalist and atheist (this was quite remarkable in those days of intense religiosity of revolutionary patriots), he made a comparative study of the revolutionary theories of Russia, Ireland and Italy and took little tune in making the ultimate choice in favour of Marxism. Whether in jail or out of it, he successfully inspired his comrades to study, think and discuss. To make the broad masses politically conscious, he used to deliver instructive lectures with the help of magic lanterns.

Even as Bhagat Singh and his dose associates were advancing towards the path of militant mass struggles, the still waters of nationalist politics began to ply. The immediate provocation came from a government announcement in November 1927 that an all-white commission will be sent to India to recommend whether the country was ripe for further constitutional progress and, if yes, on what lines. The non-inclusion of any Indian in this commission headed by Mr. Simon was widely regarded as a national insult and it was boycotted by the Congress, the Muslim League led by Jinnah, the Hindu Mahasabha and many others. When the Simon Commission landed in Bombay on 3 February 1928, massive black-flag demonstrations, mammoth rallies and numerous other forms of protest were organised everywhere in India and all major cities and towns observed complete hartal. “Go back Simon” became the angry slogan of every Indian, and the protests raged with increasing force and numerous creative forms[2] throughout the year and into the next. The repressive machinery of the state was set in full motion. While leading a protest rally at Lahore, the veteran freedom fighter Lala Lajpat Rai was mercilessly beaten up by the police and after 16 days he succumbed to the injuries on November 17, 1928. This dastardly murder of Sher-e-Punjab compelled Bhagat Singh and his comrades Chandrasekhar Azad and Rajguru to take up the pistol once again to mete out capital punishment to Saunders, a police official responsible for the murderous attack on Lajpat Rai. This was on 17 December, 1928. A HSRA poster declared : “... we regret to have had to kill a person, but he was part and parcel of that inhuman and unjust order which has to be destroyed.”[3]

After the successful action, the HSRA struck again in a totally different way. On 8 April 1929 Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt hurled small, relatively harmless bombs and bunches of leaflets from visitors’ gallery in the Central Legislative Assembly to record their protest against the passage of the notorious Public Safety Bill[4] and Trade Disputes Act. As planned, they courted arrest so as to use the trial courts for propagating their new politics of revolution by the masses. Shortly, Sukdev, Rajguru and many others were also arrested and conspiracy cases launched against them. With death-defying patriotic songs, slogans like “Down with Imperialism”, “Inquilab Zindabad”, “Long Live the Proletariat” and with fervent political speeches, the accused enthralled and roused the entire nation. As expected Bhagat Singh, Sukdev and Rajguru was sentenced to death and others to long terms of imprisonment.

Meanwhile, at the other end of the political spectrum two important events were taking place. One was the famous Bardoli Satyagraha in Surat District of Gujarat against a 22% hike in land revenue. Based on some six years of constructive work and led by Vallabbhai Patel, a very talented campaigner and organiser who acquired the title ‘Sardar’ from the people of the area, the satyagraha was enormously successful in uniting the land holding patidars or peasants and also in mobilising the tribal dalit-serfs known as kaliparaj (meaning the black people) who were misled into believing that the satyagraha also served their interest. The movement started in early 1928, and soon became a national issue drawing support from almost every quarter. Late in the year the government beat a retreat and instituted an enquiry committee which reduced the hike in land revenue to 6.03%. As Sumit Sarkar informs us, one of the reasons why the government thought it wise not to resort to repression was that the communists, who were then leading the historic Bombay textile strike, would then use it to call a successful general strike.[5]

The other important happening was the All-parties Conference which met in February, May and August 1928 to formulate a scheme of constitutional reforms that would be acceptable to all Indians. This exercise was in response to a taunting challenge thrown up by the Secretary of State Birkenhead that the quarrelling Indians were incapable of drafting such a document unitedly. The AITUC, the CPI and the Workers’ and Peasants’ Party (Bombay) were also invited to the meetings as representatives of labour (see Text VI21 for the WPP’s open letter to the conference). The meetings culminated in the “Nehru Report” (named after Motilal Nehru), i.e., a scheme which opted for Dominion Status along with a full set of constitutional provisions. This was strongly denounced by all leftist elements within and without the Congress. In November 1928 S Srinivasa Iyengar (who had just returned from the Soviet Union), Jawaharlal Nehru and SC Bose set up the “Independence For India League” which aimed at “complete independence” and “a socialist revision of the economic structure of society”. At the Calcutta session held the next month, the junior Nehru and SC Bose supported by communist delegates[6] and others pressed for Puma Swaraj or complete independence as opposed to the Gandh-i-Motilal proposal of dominion status. After much debate the latter proposal was carried, but simultaneously it was decided that if the government failed to adopt a constitution based on dominion status by the end of 1929, the Congress would go a step further by adopting complete independence as its goal and launching a civil disobedience movement to attain that goal. A memorable event of this Calcutta session was the visit of a 20,000 strong (50,000 according to Pattavi Sitaramaiah, the official historian of the Congress) workers’ contingent led by communist trade union leaders. While the workers were proceeding to the venue of the session, SC Bose arrived there on horseback at the head of a Congress volunteer force and tried to disperse them. But the workers reached their destination, intervened in the conference and, supported by the leaders like Jawaharlal, declared the resolve for Puma Swaraj before leaving the pandal.

Even as the stage was thus being set in India for a new round of confrontation with British imperialism, at international level the “League Against Imperialism” was founded at Brussels in February 1927. The League was a communist-sponsored but broad-based platform that united the national liberation movements in Asia, Africa and Latin America on the one hand and the militant workers’ movements in the imperialist countries on the other. Jawaharlal Nehru attended the Brussels Congress of the League as the representative of the Indian National Congress and was elected to its Presidium and also to the Executive; on his advice the INC became an “associate member” of the League (that is, committing itself to support only those decisions and programmes of the League as it thought proper). When Nehru returned to India in late 1927 after a visit to Soviet Union, he began to preach his youthful conviction in socialism on almost every occasion, particularly before the youth and the working class. With his great oratorial power he definitely contributed a lot in creating a general curiosity in and sympathy for socialist ideals in the new generation.

Two major vehicles of the leftward turn that the Indian polity was going to take in this period were a new youth movement and a surge in working class movement. The latter demands separate discussion; as regards the former, mention has already been made of the pioneering role played by Bhagat Singh’s NBS. But it was in course of the “Go Back Simon” agitation that a new, pro-people youth movement inspired by socialist ideals spread in Punjab Bengal, Bombay and elsewhere. Many future leaders of the CPI and the Congress Socialist Party (CSP) emerged from these youth organisation — for instance, Sohan Singh Josh and Abdul Mazid (Punjab), Indulal Yagnik and Yusuf J Meherally (Bombay) and so on.

Role of CPI in national politics

The CPI intervened in the national political scene both by means of independent political initiatives and through UF work within the Congress. Of the former there were three main vehicles. First, it played a very active role in the trade union movement, developed a strong communist faction within the AITUC and thus built up the Party's independent mass base. Particularly noteworthy in this connection is the great six-month-long Bombay Textile strike of 1928 which, along with anti-Simon agitation, marked the beginning of the crucial turnaround from the six-year-lull in mass movements to the next prolonged high tide (1930-34) and thereby earned for the proletariat and its party a special place in the freedom movement. Second, it founded Workers’ and Peasants’ Parties (WPPs) in different provinces to mobilise and train all fighting elements from within and without the Congress and to take independent political initiatives. Third, through an unbroken series of articles, notes etc. published in a number of English as well as Indian language magazines and also through numerous leaflets, pamphlets and manifestoes the CPI and the WPPs put forward their distinct political positions, calls etc. on every important occasion — be it a Congress or AITUC session, an act of repression or shrewd manoeuvre on the part of the British government, struggles launched by any section of society, the death of a national or international leader, a communal riot or other mishap - what not. These propaganda materials, a selection of which we reproduce in Texts VI17 to VI21, served to educate the people about an alternative path of freedom movement vis-a-vis the Congress path of passive resistance.

As regards UF work, communists made very effective use of the overall left shift in Indian politics (e.g., the left current within the nationalist movement as represented by Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose, the emergence of youth leagues and working class militancy, the activities of Bhagat Singh and his associates, etc.) to augment communist presence and develop left blocs at all levels of the Congress. Communists became members in the AICC and many provincial committees (e.g., in 1927 three members of the WPP of Bengal were elected to the BPCC), most notably in Bombay. There are numerous instances of a close cooperation between communists and the left-wing Congressmen against the Congress right-wing. Thus in the Madras session of the Congress (December 1927), the resolution declaring complete independence as the accredited goal of the Congress was moved in the subjects committee by KN Joglekar seconded by Jawaharlal arid was passed by an overwhelming majority. In the open session the same resolution was passed unanimously, this time moved by Jawaharlal and seconded by Joglekar. Just after the session was over, a “Republican Congress” was held in the same pandal by the left-leaning delegates, Jawaharlal was elected President and Muzaffar Ahmad one of the three secretaries. Ahmad was elected because he along with Philip Spratt[7] authored and published, on behalf of the WPP of Bengal, the “Manifesto of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Party to the Indian National Congress, Madras, 1927” (Text VI20) which was distributed at the Madras session and immensely appreciated by left-leaning Congressmen with republican ideas. As the facsimile of the its front cover shows, the Manifesto answered the most urgent questions facing the national movement at the time by cogently formulating a set of positive slogans (particularly that of a constituent assembly based on universal suffrage) and means of struggle (see Appendix to Text VI).

This radicalisation of a section of the Congress, however superficial, was denounced by the right wing headed by Gandhi, who rejected the resolution of complete independence passed at the Madras session as “hastily conceived and thoughtlessly passed” and wrote to Jawaharlal : “you are moving too fast.”[8] The fight between the two sections continued into the Calcutta session held after a year, where the communist delegates supported Jawaharlal and SC Bose in the latters’ attempt to make the Congress adhere to the Madras resolution of complete independence. But whereas in Madras Gandhi was absent, in Calcutta he led the right wing and, as seen earlier, a compromise formula was arrived at which took the Congress back to its normal Gandhian track.

Notes:

1. See India’s Struggle For Independence 1857-1947. Ed. by Bipan Chandra, Penguin Books (1989); p 254

2. For Example, in Lucknow where some loyalist elements organised a reception for members of the Simon Commission and the police made it difficult to approach the place with black flags, kites and balloons sporting the slogan “Go Back Simon” were flown to carry the message through. When the Commission travelled by train from Lotvaia to Poona, some young men boarded a truck, drove just beside the compartment carrying the members and waved black flags at them all along the journey.

3. See India's Struggle For Independence, 1857-1947, op. cit, p 249

4. The Public Safety Bill was basically an anti-communist measure designed to enable the government to summarily deport “undesirable” and “subversive” foreigners like Philip Spratt who were organising the Indian labour. It was opposed by all sections of nationalists including men like MM Malaviya and Motilal Nehru. The other Act aimed at curbing militant trade unionism.

5. See Modern India, op.cH, p 278 for the Bombay governor’s letter to the Secretary of State, where the former expressed such apprehensions on the basis of police reports.

6. Communist presence in Congress sessions and Congress Committees went on increasing till the UF policy was abandoned in 1929.

7. George Allison, Philip Spratt, Fazl Elahi (alias Qurban) and Benjamin F Bradley were sent to India during 1926-27 by CPGB for helping the Indian communists. Among them, Spratt and Bradley could avoid arrest for a longer period and played a more effective role.

8. For details, see G Adhikari, Vol. IIIC, p 432-33

Workers’ And Peasants’ Parties

During the period under review (1926-early 1929) WPPs sprang up in Bengal, Bombay, Punjab, UP and Ajmer-Marwara with basically the same orientation and programme, but the actual process of their emergence displayed interesting regional variations. Before we generalise, therefore, let us study the experiences separately.

Bengal

The “Labour-Swaraj Party of the Indian National Congress” was founded in Calcutta on 1 November, 1925 by Hemanta Kumar Sarkar, Kazi Nazrul Islam and a few others. Its moving spirit was Nazrul, an ex-soldier of the British Indian army fighting in foreign lands during the first world war and the firebrand “rebel” poet of Bengal. From the early twenties he wrote highly inflammatory patriotic poetry and prose and was sentenced to one year’s RI in January 1923 for publishing one such poem in Dhumketu (the Comet), a literary magazine edited by him. Sarkar was a prominent left-swarajist and many others like him supported the Labour-Swaraj Party. The party’s “constitution” defined its object as “the attainment of swaraj in the sense of complete independence of India based on economic and social emancipation and political freedom of men and women”, with “non-violent mass action” as “the principle means of the attainment of the above object”. The “Policy And Programme” laid particular stress on organising workers and peasants and put forward a complete charter of the immediate as well as ultimate demands of these “eighty per cent of the population.”[1]

From 16 December 1925 the party’s weekly organ Langal began to appear under the able editorship of Nazrul. It was very popular, particularly for Nazrul’s poems, but at the same time made critical comments and analyses on political currents. In early 1926 Muzaffar Ahmad associated himself with the magazine and the party, which was now renamed as Bengal Peasants’ And Workers’ Party. Langal in its various issues carried the documents of the first communist conference of 1925 as well as many other materials that directly or indirectly popularised communist ideals. It was discontinued after 15 April 1926 but reappeared from 12 August the same year as Ganavani (Voice of the People), this time with Ahmad himself as editor. Whereas Langal had published summaries of Marx’s two articles on India, Ganavani serialised the Manifesto of Communist Party by Marx and Engels. Both the papers, particularly the later one, acted as mouthpieces of the all-India communist movement. Thus Ganavani published a review of Dange’s Gandhi Vs. Lenin and reported on workers' movements in Assam, Kanpur and around Calcutta. The magazine stopped in October 1926 for lack of funds, reappeared from April to October 1927 and then stopped for good owing to the same reason.

The Peasants’ And Workers’ Party of Bengal (PWPB) held its second conference in Calcutta on February 19 and 20, 1927 and adopted a new programme which was exactly similar to the one adopted by the WPP of Bombay a little earlier (see below). Right from the days of the Labour Swaraj Party it kept its membership open to Congressmen provided they accepted its constitution and programme; similarly it encouraged its members to become members and office bearers in the Congress. The party’s TU work was concentrated among jute mill and railway workers around Calcutta; it organised district conference of peasants in Nadia and Bagura. In its third conference held in Bhatpara (an industrial area north of Calcutta) on 31 March – 1 April 1928, the party was renamed as Workers’ and Peasants’ Party of Bengal.

Bombay

In Bombay province, a “Congress Labour Party” emerged from within the Congress in November 1926. It renamed itself as WPP in February 1927 and adopted a programme (Text Vs) that corresponded to the resolution adopted by the CEC of CPI in its January meeting. The programme clarified that the WPP was an independent political party based on the class organisations of workers and peasants, but working also inside the Congress to form a left bloc there; it strove to form a broad anti-imperialist front for attaining “complete national independence” while its “ultimate object” was socialist swaraj. Among its office-bearers three were AICC members (Joglekar, Nimbkar and Thengdi) and three members of the CEC of CPI elected at Kanpur (Ghate, Joglekar and Nimbkar). Apart from these three all others, i.e., the majority were not communists (Mirajkar joined the CPI later but not the others). The WPP was thus really a broad-based mass political organisation. The party’s constitution declared that “membership to the Indian National Congress is considered highly recommendatory.”[2]

The WPP (Bombay), from the very outset, engaged itself very seriously in trade union activities (particularly among textiles, railways, municipal and dock workers) and at the same time worked within the Congress with a definite purpose. When the AICC met at Bombay from 5 May 1927, the WPP through Joglekar and Nimbkar presented before it a programme of action which the Congress should take up (See Text V4). The programme put forward the slogan of complete independence and called for mass civil disobedience movement — both of which were rejected at the time but taken up by the dominant Congress leadership more than a couple of years later.

An idea of the daily activities of the WPP can be had from the annual report of its first annual conference held in early 1928. In addition to energetic trade union work, during 1927 the party “organised the following meetings: Lenin Day (22 January), Welcome to Saklatvala (February), Welcome to SA Dange (on his release – 24 May), first ever May Day in Bombay, welcome to Shaukat Usmani on his release (July), 10th Anniversary of the Russian Revolution (7 November), and the protest meetings against the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti in USA.”[3] The party organ Kranti (Marathi, meaning revolution) was published from May to September, 1927.

Punjab

The story of Punjab was much different. A Punjabi monthly Kirti (Gurmukhi, meaning worker) was started by Santokh Singh, a Ghadr Party leader, in February 1926. It came under the editorship of Sohan Singh Josh in 1927 and on 12 April 1928 the inaugural conference of the Kirti Kisan Party (KKP) was held at Jalianwala Bagh in Amritsar. A number of militant nationalist leaders of Punjab and the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) was present in this conference, such as Dr. Satyapal, Bhag Singh Canadian, Bhai Gopal Singh etc. Main organisers of the party included Josh, Firozuddin Mansur, Mir Abdul Mazid and Kedarnath Sehgal. Kirti became the party’s political-cum-cultural organ and its Urdu edition also began to be published. The KKP decided to fight for the "establishment of the national democratic independence through revolution”[4], as SS Josh later put it in his statement in the Meerut case. Josh was elected the general secretary with Abdul Mazid as joint secretary.

The KKP was involved in trade union activities — particularly among the woolen mill workers of Dhariwal — and published the Urdu weekly Mehanatkash (Toiler) devoted to this purpose. It also strove, with some success, to win the toiling peasantry away from the landlord-Shaukar-domiriated “Zamindara League” and for this purpose held its second conference (September 1928) at Lyallpur, a stronghold of the League. The KKP differed from the WPPs of Bombay and Bengal on one important point: the attitude to the Congress. As SS Josh pointed out a statement in the Meerut trials,

- “It was openly a revolutionary body of the militant workers and peasants, who being disillusioned by the Congress defeatist politics, had risen in revolt against it. It had nothing to do with the Congress and was in no way connected with, or under the influence of, the Congress. In fact this was a party diametrically opposed to the Congress. ... No man professing to be a Congressman was allowed to use the platform of the party.”[5]

Josh also declared that the party’s first president Raizada Hansraj was “chucked out of the party” when he was found to he “a Congressman”. The party, however, “was not a communist body” though “a number of communists were working side by side with the non-communists”.[6]

UP and Delhi

This WPP of UP and Delhi was founded at a conference held in Meerut in mid-October, 1929. The conference was presided over by Kedarnath Sehgal and attended by communist leaders from other provinces, such as SS Josh, Philip Spratt, Muzaffar Ahmad. PC Joshi, who later became the General Secretary of the CPI, was elected the secretary of the WPP. The party published the Hindi weekly Krantikari (Revolutionary) and concentrated on propaganda work by means of meetings, conference, pamphlets etc. The party’s political character was described by PC Joshi in his Meerut case statement in the following words:

“The WPP was a mass anti-imperialist party; it was a party of those classes whose interests are opposed to imperialism in a revolutionary manner. Its membership consisted of the affiliated trade unions, peasants’ unions, revolutionary youth organisations and revolutionary intellectuals.”[7] Shortly after foundation, the party formed branches in Gorakhpur, Jhansi and Allahabad.

The WPP of India

The communists working in the different WPPs in various provinces began to plan an all-India conference early in 1920 and it was actually held in Calcutta in the last week of December the same year, i.e., just prior to the session of the Indian National Congress. The conference was quite well-prepared and well-organised. It opened with the “International” (in Bengali version) sung by Kazi Nazrul Islam and others. Delegates from all the four provincial level WPPs were present and also many TU representatives and other activists and sympathisers. The president's speech was delivered by SS Josh (See Text V5). Greetings were sent by a number of international organisations including the League Against Imperialism (which also sent a fraternal delegate but he was arrested on arriving in India). J Ryan of the New South Wales Council of Trade Unions and BF Bradley, representing the Amalgamated Engineering Union and the CPGB delivered speeches. On the third day of the conference, a message was received from the ECCI (Text V8) which was not discussed and did not have any effect on the proceedings. We shall come back to this document a bit later. There were lively debates and discussions on the major draft documents which included the Political Resolution (Text V6), On TU Movement and the Constitution (Text V7).

The conference (also mentioned as congress in some of the documents) unanimously resolved that the All-India WPP be affiliated to the, League Against Imperialism. A 16-member national executive committee was elected with four members nominated by representatives of each of the four provinces (Bombay, Bengal, Punjab, UP) and then elected by the conference unopposed. There was a dispute, however, among Bengal comrades on choosing their nominees, and some of them staged a walkout. After the formation of the all-India party, the erstwhile WPPs were regarded as provincial committees of the former.

Interesting events of the conference included : the presence of Nazrul Islam who sang two songs composed by himself apart from the “International”; the presence of Bhagat Singh (as recorded by SS Josh in his memoirs on Bhagat Singh); and a procession of all the delegates, leaders and visitors to the “Congress Nagar” (venue of the forthcoming Congress session) during a break between two sessions.

Notes:

1. The complete texts of the “Constitution” and “Policy And Programme” are available in G Adhikari, Vol. II, pp 682-86

2. See G Adhikari, vol. IIIB, p 33

3. See G Adhikari, Vol. IIIB, p 39

4. See G Adhikari, Vol. IIIC, p 89

5. See G Adhikari, Vol. IIIC, p 285-86

6. bid.

7. See G Adhikari, Vol. IIIC, p 90-91

WPP Vis-a-vis CPI

After its foundation at the fag end of 1925, the CPI routed all its anti-imperialist agitations (e.g. against Simon Commission), TU activities and propaganda work through the WPPs. Originally and basically the WPPs evolved as a left pole in the national movement and the first batch of communists got involved with them more out of political instinct than according to any theoretical framework.[1] However, the communists were quick to bring these organisations under their guidance, imparting greater specificity of purpose to, and creating a mass base through, the latter. PC Joshi, SS Josh and many other prominent and not-so-prominent leaders and cadres started their political life as WPP activists or leaders and became communists subsequently.

During this period, was there any effort to strengthen the communist party as such? Let us briefly review the relevant facts in a chronological order.

1. The “Working Council of the CEC” (i.e., the office-beareres) assembled in Bombay from 16 to 18 January 1927 to (i) meet Shapurji Saklatvala and (ii) discuss the proposal of a second communist conference. Saklatvala arrived in Bombay on 14 January and was warmly welcomed by CPI leaders who frankly sought his “suggestions and lead” to make the approaching conference (then planned to be held at Lahore) a success. In response, Saklatvala issued a statement to the press to the effect that he would not preside over the conference of a communist party which is not affiliated to the CI. This was immediately and strongly protested by the joint secretaries SV Ghate and JP Bagerhatta: “We in India have every right to form a communist party and to contribute in our own way to the cause of international communism. The question of international affiliation comes later. ... All the same, in spite of your non-cooperation with us, we extend [you] our hearty welcome to our conference at Lahore.” The ill-feeling thus generated was overcome within a few days when Saklatvala, after further discussions with CPI leaders and Philip Spratt and George Allison, reversed his position and expressed his readiness to give all help “to make such a conference a success so that out of your efforts a regular and properly authorised communist party of India may take birth.”[2]

This episode finds reflection in the seventh resolution of the “Working Council of the CEC” (Text III10) because Saklatvala’s second letter, from which we have quoted above, reached the CPI leaders a bit later. Muzaffar Ahmad, JP Bagerhatta, SV Ghate, Krishnaswamy lyengar, RS Nimbkar and Shamsuddin Hassan were present at the meeting. Three major immediate tasks were decided upon (a) holding a party conference in March in Lahore to be presided over by M Ahmad, (b) drafting a new party constitution and (c) organizing a WPP in Bombay. The proposed conference did not materialise, but an extended CEC meeting was held in May 1927.

2. The May 1927 extended meeting of the CEC adopted an annual report, a new party constituion and a few resolutions on the party programme and on certain other points. All these are collected under Text IIIn, which is largely self-explanatory. Let us, therefore, note here only some important outcomes and salient features of this meeting.

The annual report stresses the national roots of the CPI and expresses an ardent desire to overcome the Party’s historical limitations. Although three “non-official organs”, i.e., magazines of WPPs were being published, the necessity for a Party organ and for that purpose the Party’s own printing press, was underscored. But the section on the government’s attitude shows that even after Peshawar and Kanpur cases and other repressions, the Party still nurtured some legalist illusions : “nothing can, as yet, be said about their attitude towards us”. The meetings was held openly and the names as well as addresses of office-bearers were made known to all.

The constitution, despite a number of weaknesses, is definitely an improvement over the 1925 one adopted at Kanpur. A detailed organisational structure is formulated, party discipline is emphasised, rules for fractional work etc. is laid down. Democratic centralism is not mentioned, but a compact all-India collective leadership is formed (the presidium plus the, general secretary) and a central office set up. It is interesting to note that the CPI is not described as a “section of the CI”, as was the norm in those days, and as MN Roy had instructed on behalf of the Comintern just after the Kanpur conference; but member ship is limited to “those subscribing to the programme laid down by the CI”.

Among the various resolutions adopted, perhaps the most notable are the minimum programme, the call to all party members to enter the Congress and the decision to try and form a republican wing in the AICC. Interestingly within half a year a “republican congress” session was held, as we have already seen, on the initiative of Jawaharlal and some others, in which communists played an important role.

All things considered, this was the most significant CEC meeting in the pre-Meerut period.

3. An informal meeting of some CEC members and a few WPP leaders was held in the fag end of December 1927 in Madras, where they met on the occasion of the Congress session. Unlike the earlier meetings, this one was secretly held. The main political discussion centred round the holding of a “congress” in Calcutta to set up an all-India WPP — drafting political and organisational theses for that, practical arrangements etc. The “congress” or conference was planned to be held between February-March but actually took place, as we have seen, in December 1928. The meeting also took action against party members associated with communal organisations or journals brought out by the latter. For instance, Hasrat Mohani, who was simultaneously a member of the Muslim league, was asked to quit the same but he preferred to resign from the Party while KN Joglekar, concurrently a member of the Brahman Sabha of Bombay, was asked to resign from the latter and he obliged.

4. The CEC met again for three days just after the WPP conference. G Adhikari, SS Mirajkar, DB Kulkarni and SS Josh were admitted as members; the name of PC Joshi also came up, but it was decided to leave it for the time being. Hasrat Mohani and SD Hasan were expelled. A 10 member Central Executive was formed, with five from Bombay (Mirajkar, Dange, Nimbkar, Joglekar, Ghate), three from Calcutta (M Ahmad, Abdul Halim and Samsul Huda) and two from Punjab (Abdul Majid and SS Josh). Ghate was elected General Secretary. It was decided that in between two CE meetings the five in Bombay would function as the CE with a quorum of four which must include the GS. The Party’s head office was to be in Bombay. The Party’s central organ was to be published from Calcutta — the responsibility was given to Ahmad. Ahmad was also selected as the party’s delegate to the ECCI. It was also decided that plan for enrolment of new members should be drawn up.

Much more crucial than these organisational matters was a prolonged discussion on the theses of the Sixth Comintern Congress which concluded two months ago. These theses, as we shall presently see, had strongly criticised the practice of WPP and the policy of close cooperation with the Indian National Congress; great stress was laid on the independent role of the communist party in the arena of class struggle. After discussion and debates, it was decided that the new Comintern guideline “should be taken up as a basis and to be changed according to the conditions in India” and that “possibilities of an open party should be tested”[3]. This critical assimilation of international guideline resulted in the issuance of a “Manifesto of CPI To All Workers” (Text III12) which reaffirmed the need for WPP as “a necessary stage” but put special emphasis on the need to develop class struggle and to build the communist party as the party of the working class. Shortly afterwards, i.e. in early 1929, a new constitution was framed (Text III13) which for the first time formally decalred the CPI to be “a section of the CI”.

From this account of the four meetings a definite trend becomes clear. During the first half of the three-year-period (approx.) between the first communist conference and the Meerut arrests, the handful of communists seriously strove to overcome the historical limitations of the new-born CPI — witness the efforts to organise the second communist conference and to set up a party press, the decisions and documents adopted at the May 1927 meetings, etc. But then with the success and spread of WPPs, the primary attention was shifted to them, while the communist party as a distinct entity and the special party tasks receded more and more into the background. Upto 1926, manifestoes to the annual sessions of the Congress — whether drafted and sent from abroad by Roy (to Ahmedabad and Gaya sessions for instance) or by the CPI after its foundation (to the Gauhati session of December 1926) — had always been issued in the name of the CPI, but from late 1927 all such interventions began to be made in the name of WPPs. Thus the “Manifesto” to the Madras session (December 1927), the “Open Letter” and “Statement” to the all-parties conference (1928) and similar propaganda materials were issued in the aame of WPP. The leadership no longer cared for a party organ — the otherwise successful and open WPP magazines were deemed sufficient. No attention was paid to the ideological and organisational aspects of party building (recruitment of large number of party members appropriate to the expansion of mass work, formation of party committees, cells etc. at various levels and so on) or to the painstaking task, which was being repeatedly emphasised by Roy on behalf of the CI, of building an underground structure. For all practical purposes, the communist party was gradually becoming an appendage of its own creation — the WPP[4].

This state of affairs was largely changed after party leaders came to know about the new directives of the Sixth Congress of the CI through its message to the WPP conference of December 1928 and through other documents[5]. The change will be evident from the above description of the fourth CEC meeting : though the WPP was not discontinued as implicitly asked by the Comintern, the role of the communist party was rediscovered, so to say, and this was reflected in the new manifesto and the new constitution (Text III12 and III13 respectively). Unfortunately, this renewed experiment for properly combining a broad democratic and anti-imperialist organisation (the WPP) with a consolidated communist party was cut short by the Meerut arrests (March 1929). And the next five-year period was marked by political confusion and organisational chaos.

Before we conclude this chapter, a few words on the discontinuation of the WPP are necessary.

The Indian communists never formally disbanded the WPP, nor took any decision to do so. Actually they held the second conference of WPP in December 1929 when they met in Lahore (the venue of that year’s Congress session), though in the shattered state of the organisation it could only be a poor successor to the first all-India conference. Again the Kirti Kisan Party of Punjab maintained its independent existence, though not under communist control, upto 1933. So it is wrong to suggest that the WPP was dissolved simply by the order of the Comintern. The fact of history is that the discontinuation of the WPP in the 1930s was the combined result of three factors: intensified police repression on the WPPs and discontinuity of leadership after the wholesale Meerut arrests; the Congress leadership’s regained credibility and capacity to attract militant forces during the Civil Disobedience Movement in the early thirties (this was important in so far as WPP success was largely proportionate to Congress failure and resulting disillusionment); and most importantly, the new, post-Sixth-Congress political line of stressing the independent role of the communist party to the extent of practical denial of anti-imperialist united front, particularly the implicit instruction to disband the WPP.

If there are so many evidences to support the allegation that Indian communists lacked creativity and blindly followed “international directives”, there are at least a few to prove the opposite. And one of them was the WPP. The Indian communists were trying to develop this as a popular form for communist mass work. If in the process they started losing the communist perspective, as indeed they did, the duty of the CI was to criticise and persuade the CPI to rectify this deviation. But the way it instructed the CPI to stop the practice altogether, without so much of a comradely discussion, scuttled the very process of Indianisation of the communist movement. This was but the first instance of arbitrary interference on behalf of the Comintern — many more were to be experienced in the years to come. The particularly deplorable thing about such directives was that they were often coloured by shifts in Soviet foreign policy or inner-party developments in the CPSU (struggle against right opportunism in this case).

Notes:

1. Although the Comintern had in 1925 called upon the communists of the east to form WPPs and “to work hard and consistently within these parties -always maintaining their own political independence — in order to turn them into political organisations of the anti-imperialist front” (See Outline History of the Communist International — Progress Publishers (Moscow, 1971) p 232) and MN Roy in a series of articles, letters, etc. (see Text V9) dwelt on this theme at length, these do not seem to have determined the actual practice of the WPPs.

2. For details of the episode, see G Adhikari, Vol. IIIB, pp 3-6. Saklatvala toured a number of cities, addressed huge meetings and exchanged open letters with, and also met, MK Gandhi. His speeches were widely reported and he was accorded a warm welcome by citizens of Bombay, Calcutta etc.

3. See Q Adhikari, Vol. NIC, p 783

4. According to Horace Williamson, Director of IB, “To Such a pass had things come in May 1928, that Ghate seriously suggested that the Workers’ and Peasants’ Party should control the Communist Party — a complete reversal of the orthodox procedure prescribed in Moscow.” Williamson, however, does not give the source of this bit of information. See his India And Communism (published by Editions Indian, 1976) p 127.

5. It is in the next chapter that we shall discuss the Sixth Congress deliberations on WPPs, for these cannot be understood in isolation from the other issues discussed there.

The Sixth Congress of Comintern

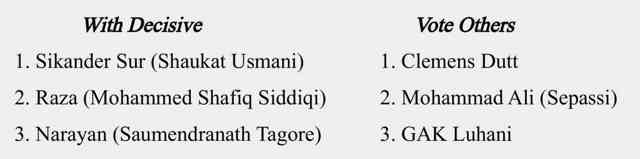

The long-drawn sessions of this Congress (July 17 to September 1, 1928), the first one to be held after the new Soviet and Comintern leadership headed by Stalin had consolidated itself, marked a watershed in the evolution of strategy and tactics for the international communist movement in general and that in colonies and semi-colonies in particular. But before we come to that, let us note the names of the Indian delegates to this Congress:

Sikander Sur was included in the presidium and his speeches supporting the official line were reported in Inprecor. According to some sources there was another Indian delegate named Habib Ahmed. Anyway, the important thing to note is that none of these delegates carried a proper official mandate from the CPI — they arrived in Moscow and attended the Congress on individual or factional basis. Tagore, for example, had been staying in Moscow since 1927 as a representative of the WPP of Bengal.

MN Roy had been under medical treatment in Berlin and therefore could not answer the political charges brought against him in this Congress. He had been asked by the Comintern to prepare a draft on the Indian situation and he did so in 1927 itself; but this was not placed before the Congress although Kuusinen in his report (Text II15) quoted particular passages to attack Roy.

Held at a crucial juncture of the international communist movement, the Sixth Congress heard a number of reports,

co-reports and debates on many vital questions of theory, strategy and tactics. Of these, we will be selectively discussing those that are connected with questions of revolutionary movements in colonies and semi-colonies[1]. India figured very prominently in the discussions on these questions, for the 1927 setback in the Chinese revolution had created a great concern for preventing the repetition of the CPC’s mistakes in India.

This Congress adopted a general programme for the international communist movement as a whole (Programme for short). Regarding the colonial and semi-colonial countries it said:

- “The principal task in such countries (China, India etc.) is, on the one hand, to fight against the feudal and pre-capitalist forms of exploitation, and to develop systematically the peasant agrarian revolution; on the other hand, to fight against foreign imperialism for national independence.

- “... the central task is to fight for national independence.

- “In the colonies and semi-colonies where the proletariat is the leader of and commands hegemony in the struggle, the consistent bourgeois democratic revolution will grow into proletarian revolution in proportion as the struggle develops and becomes more intense.”[2]

The Programme, like other documents of the Congress, repeatedly emphasised the task of agrarian revolution, asking the communists in the colonial and semi-colonial countries to “rouse the broad masses of the peasantry for the overthrow of the landlords and combat the reactionary and medieval influence of the priesthood, of the missionaries and other similar elements.” It stated :

- “In these countries, the principal task is to organise the workers and the peasantry independently (to establish class Communist Parties of the proletariat, trade unions, peasant leagues and committees and—in a revolutionary situation, Soviets etc.), and to free them from the influence of the national bourgeoisie, with whom temporary agreements may be made only on the condition that they, the bourgeoisie, do not hamper the revolutionary organisation of the workers and peasants and that they carry on a genuine struggle against imperialism”[3]

The ‘Decolonisation’ controversy

As we have seen before, right from his 1922 work India In Transition, MN Roy had been trying to develop, a theory on the post-war industrialisation of India made possible by the British imperialists’ compulsion to export considerable amounts of finance capital to India. The theme was further developed in his The Future of Indian Politics (1926) and a number of other writings; Rajani Palme Dutt in Modern India (1926) also put forward a more or less similar analysis of the economic scene in India. Finally, in his unpublished Draft Resolution on the Indian question (to which we have referred earlier), Roy wrote:

- “The implication of the new policy is a gradual “de-colonisation” of India, which will be allowed to evolve out of the state of “dependency” to “Dominion status”. The Indian bourgeoisie, instead of being kept down as a potential rival, will be granted partnership in the economic development of the country under the hegemony of imperialism. From a backward, agricultural colonial possession India will become a modern, industrial country — a “member of the British Commonwealth of free nations”. India is in a process of “decolonization” in so far as the policy forced upon

- British imperialism by the post-war crisis of capitalism abolishes the old antiquated forms and methods of colonial exploitation in favour of new forms and new methods. The forces of production, which were so far denied the possibilities of normal growth, are unfettered. The very basis of national economy changes. Old class relations are replaced by new class relations. The basic industry, agriculture, stands on the verge of revolution (The prevailing system of land ownership which hinders agricultural production is threatened with abolition). The native bourgeoisie acquires an ever-growing share in the control of the economic life of the country. These changes in the economic sphere have their political reflex. The unavoidable process of gradual “de-colonisation” has in it the germs of disruption of the empire. As a matter of fact, the new policy adopted for the consolidation of the empire — to avoid the danger of immediate crush [crash?] — indicates that the foundation of the empire is shaken. Imperialism is a violent manifestation of capitalist prosperity. In this period of capitalist decline its base is undermined.”[4]

And again:

“Indian bourgeoisie outgrows the state of absolute colonial suppression not as a result of its struggle against imperialism. The process of the gradual “decolonization” of India is produced by two different factors, namely, (1) post-war crisis of capitalism and (2) the revolutionary awakening of the Indian masses. In order to stabilise its economic basis and strengthen its position in India, British imperialism is obliged to adopt a policy which cannot be put into practice without making certain concessions to the Indian bourgeoisie. These concessions are not conquered by the Indian nationalist bourgeoisie. They are gifts (reluctant, but obligatory) of imperialism. Therefore, the process of “de-colonisation” is parallel to the process of “de-revolutionisation” of the Indian bourgeoisie”.[5]

Otto V Kuusinen in his report on “The Revolutionary Movement in the Colonies” (Text II15) forcefully countered this theoretical position and also its variants as expressed in the writings of RP Dutt and GAK Luhani. He argued that (i) British concessions in favour of India’s industrial growth in the post-war period was the result of certain short-term economic, political and military exigencies (e.g., intensifying trade-war with Japan and USA, the linked non-cooperation and khilafat movements, mutiny in the army etc.); (ii) only some 10 per cent of the British capital export to India was being invested in industry and the rest in government bonds etc.; (iii) given the stagnant internal market of India made up mainly of the pauperised peasantry, the scope of industrialisation was extremely limited; and (iv) the huge unproductive investments on the part of the Indian bourgeoisie (in gold, silver, savings banks etc.) was nothing but an indirect pointer to the obstacles put up by the British colonial system on the road to industrialisation.

The official Comintern view presented by Kuusinen sparked off a sharp debate in the Congress. The majority of British delegates such as Bennett, Rothstein, Page Arnot etc. spoke against the official report. They, however, did not necessarily support Roy’s formulations and there were important differences among themselves. The Indonesian delegate Padi tried to show that despite the low purchasing power of the colonial peoples, industrialisation was proceeding there at a rapid rate thanks to cheap raw materials and labour power. Among Indian delegates, Sikander Sur (who had the privilege to present a co-report after Kuusinen), predictably, supported Kuusinen and so did Raza while Narayan spoke against.

The debate on the nature, extent and political implications of industrialisation in India had, in fact, been going on from well before the Sixth Congress and continued after it. For instance, in January-February, 1928, GAK Luhani wrote an article in Communist International putting forward his own version of the decolonisation theory; interestingly, in the Sixth Congress itself he declared that he had “nothing whatever to do with the so-called decolonisation of India theory” and that he “wanted to repudiate entirely the interpretation which comrade Kuusinnen has given to our use of the term”. Then between March and June the same year, an interesting polemic took place between Eugen Varga, the noted Hungarian economist on the Comintern staff, writing in Inprecor and RP Dutt writing in Labour Monthly. However, Clemens Dutt took his position against the de-colonisation theory both in an article in Communist International in July 1928 and in the Congress itself. The Comintern position was ably defended at the Congress by, inter alia, the American delegates Pepper and Wolfe, the German delegate Remmele and Martynov who represented the CPSU. Finally, Kuusinen in his concluding speech (Text II17) offered some clarifications. When MN Roy received the relevant documents of the Sixth Congress, he issued a comprehensive statement elucidating and summing up his position on the industrialisation-decolonisation controversy. In Text II19 we reproduce extracts from this statement to the ECCI because this embodied his most mature treatment of the subject.

The debate was complicated by the existence of not two but three distinct views. First, there was MN Roy’s view that rapid industrialisation of India was leading the country towards political decolonisation via domination status and that this resulted in a lessening of the contradiction between the Indian bourgeoisie and British imperialism or even a total shift of the former to the side of the latter. Secondly, the British delegation which did not share the proposition of political decolonisation put forward the “industrialisation thesis” as an economic process. Thirdly, the Comintern view rejected both these views, saying that (i) a certain industrial development did not yet mean “industrialization”, i.e., transformation of a feudal-agrarian country into a capitalist industrialised country, which is impossible under the control of imperialism; (ii) this industrial growth actually deepened the contradiction between the Indian bourgeoisie and British imperialism (see the title of Kuusinen’s concluding speech); and (iii) the thesis of “decolonization” was theoretically anti-Marxist-Leninist and politically harmful.

Writing about it six decades later, it is easier for us to take the testimony of history and observe that Roy’s conclusions were rather hasty and far-fetched and therefore politically harmful, but he grasped the essential direction of change: the post-war industrial growth (quite remarkable by colonial standards), and progressive power-sharing (however haltingly) — which ultimately led to a semi-colonial status for India as a member of the Commonwealth. By contrast, the Comintern’s portrayal of the current Indian scene was more correct but it took a metaphysical view of Lenin’s theory of imperialism and refused to follow the real course of life. Of course, the best thing would have been to allow a healthy debate on the subject. Changes in the political relationship between imperialist countries and their colonies/semi-colonies, based on economic evolution in both (primarily the former) as well as in the world at large, was indeed an important topic of Marxist study and remains so to this day. But the way the CI rejected it all by branding it “anti-Marxist-Leninist” prevented the research and the debate from running their full course. This rigidity marked a clear departure from Lenin's dialectical method of resolving theoretical debates (remember the Roy-Lenin debate in the Second Congress) and hampered the much-required development of the Marxist-Leninist understanding of the colonial question.

The Second Colonial Theses

Eight yeas after Lenin’s colonial theses were adopted at the Second Congress of Communist International (1920), the new theses (Text II16) now put forward the following basic propositions :

1. Stage and Nature of Colonial Revolution : “Along with the national-emancipatory struggle, the agrarian revolution constitutes the axis of the bourgeois democratic revolution in the chief colonial countries.”

2. Role of different classes: While the commercial or comprador bourgeoisie directly serves the interests of imperialism, another section connected with native industry supports the national movement in a vacillating way and at times also compromises with imperialism. Overall, the colonial bourgeoisie has proved itself treacherous and is so inexorably bound up with feudal interests that it opposes not only the agrarian revolution but even any major agrarian reform. In such circumstances, the industrial proletariat must come forward to lead the bourgeois-democratic revolution. “The peasantry, as well as the proletariat and as its ally, represents a driving force of the revolution.”

3. The Key Task: Strengthening the communist parties politically, organisationally and as regards mass base; and in the particular case of India:

Politically, the “basic tasks” are “struggle against British imperialism for the emancipation of the country, for destruction of all relics of feudalism, for the agrarian revolution and for establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry in the form of a Soviet Republic.”

And organisationally : “The union of all communist groups and individual communists scattered throughout the country into a single, independent and centralised party is the first task of the Indian communists.”

4. On United Front: “The formation of any kind of bloc between the communist party and the national revolutionary opposition must be rejected; this does not exclude temporary agreements and the co-ordination of activities in particular anti-imperialist actions”, provided this proves helpful for the development of mass movement and the communists’ freedom of agitation and organisation is not restricted. Generally speaking, the communist parties in colonial countries must “demarcate themselves in the most clear-cut fashion, both politically and organisationally, from all the petty-bourgeois groups and parties.”

Despite loud protests from leaders of CPGB and some others including the Indian Tagore, the concept and practice of WPPS were rejected outright as we have seen in an earlier chapter, And needless to add, the entire theses was premised on the rejection of the de-colonisation theory.

Implications of the New Tactical Line

From the above we find that new Comintern theses did not ask the communists to cut themselves off from the national movement, but put forward two complimentary tasks. Firstly, since “bourgeois opposition to the ruling imperialist-feudal bloc”, though insignificant in itself, “can accelerate the political awakening of the broad working masses” and “indirectly serve as the starting point of great revolutionary mass actions”, communists must learn to utilise every such conflict, “to expand such conflicts and to broaden their significance, to link them with the agitation for revolutionary slogans” and so on. This is one part of the task, contained in para 23 of the theses. The second part, enumerated in para 24, is this: since parties like the Swarajists (meaning the Congress), despite their repeated betrayals, “have not yet finally passed over, like the Kuomintang, to the counter-revolutionary camp” but will certainly do so later on, the communists must expose their true character in all possible ways. Overall, the communists are thus asked to link up with and utilise the programmes of bourgeois parties; to carry on issue-based joint activities and enter into temporary agreements with the latter if necessary, but not to enter into any kind of bloc, which naturally envisages a common programme, concentrating rather on building up the independent strength of the party of the working class — the communist party — among workers and peasants. At the core of these guidelines lay an emphasis on the purity of class character (hence the disavowal of WPPs), political independence (to be manifested through the most advanced slogans and a distinct proletarian programme) and organisational consolidation of the communist party. At least so far as the CPI was concerned, these were precisely the points neglected for long and apparently the emphasis was not misplaced.

But where the directives of the Sixth Congress deviated from the Leninist line of the Second to Fifth Congresses was: the task of building a broad anti-imperialist front was practically withdrawn, only to be reintroduced at the next Congress in 1935. This five-year departure from the otherwise consistent UF policy is explained by a whole set of objectives and subjective conditions. Internationally, the CI expected an impending crash in the world capitalist economy (within a year this certainly proved correct) and a consequent leap forward in the world communist movement (this mechanical deterministic appraisal proved largely incorrect). It also visualised a fusion of social-democracy with fascism and hence the need for communists to go it alone. These overall political understandings naturally influenced the Comintern’s colonial theses too. And as regards the specific situation in colonies and semi-colonies, there was, in the first place, the great betrayal by the Kuomintang in 1927, the vacillations and compromises by the Gandhian and Wafdist (in Egypt) leaderships and the assumption (which, again, did not prove fully correct) that these parties also are bound to openly join the imperialist camp sooner or later. This made the CI rather sceptical about any united front with the colonial bourgeoisie. Secondly, in the particular case of India, the vigorous growth of working class struggle — and that even during periods of lull in the Congress-led movement — prompted the CI to overestimate the political independence and advanced role of the Indian proletariat. So it straight away put forward the task of “establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry in the form of a Soviet republic” (para 16 (a) of the theses), skirting round the complicated but vital question of united front with the native bourgeoisie.

In the Indian context, this meant not only the abandonment of the specific organisational form of WPPs working inside the Indian National Congress, but a total oppositiorrto the latter. But as the next couple of decades was to show, the INC never behaved exactly like the Kuomintang. The Chinese big bourgeoisie did enjoy state power, however incomplete, in at least some major parts of the country, and this they strove to defend, in league with imperialists, against the onslaughts of the revolutionary workers and peasants led by the Chinese Communist Party (and even then they sided with the CPC when the onslaught came mainly from the imperialist side). In India the same classes were placed in a different situation. They could hope to rule the land — and this hope and aspiration rose consistently with the growth in their economic stature — only by squeezing state power from the colonial masters. In this struggle against an incomparably stronger force they were prepared, even eager, to enlist the support of all other class forces; of course to the extent their own hegemony was not impaired. So there was enough scope for UF work in India, but this was completely negated by the Sixth Congress line. How this grave error was further magnified in the actual practice of Indian communists, we will see in the next Part of the volume.

Notes:

1. To have a brief idea of the general backdrop to this Congress and a summary of the main decisions on the colonial question., the reader will do well to first glance through Text II18 — the “Theses of the Agitprop of the ECCI”, i.e., a report by the propaganda wing of the Cl which was published after the Congress and summarised the proceedings.

2. Inprecor, December 31,1928

3. Ibid.

4. For full text of the document, see G Adhikari, Vol. IIIC, pp 572-606

5. Ibid.

The Meerut Conspiracy Case

The year 1928 presented the British government with a series of nightmares : the grand resurgence in workers’ movement, their increased involvement in national politics and the very prominent role of communists in both these development; the rapid spread of WPPs and their consolidation at the national level; the revival of mass anti-imperialist movement provoked by the Simon Commission; the revolutionary activities of Bhagat Singh and his comrades; the last but not the least, the coming closer of communists and a section of the nationalist leadership. In 1929 the Raj struck back. Its first target was naturally the communists working through the WPPs, for they were rapidly becoming the most powerful mass stream of the national liberation movement. Thus was launched the famous Meerut Conspiracy Case, actually the most important link in a chain of repressive measures : the Public Safety Bill and Trade Disputes Bill, the prosecution of and death sentences to Bhagat Singh and his comrades and so on.

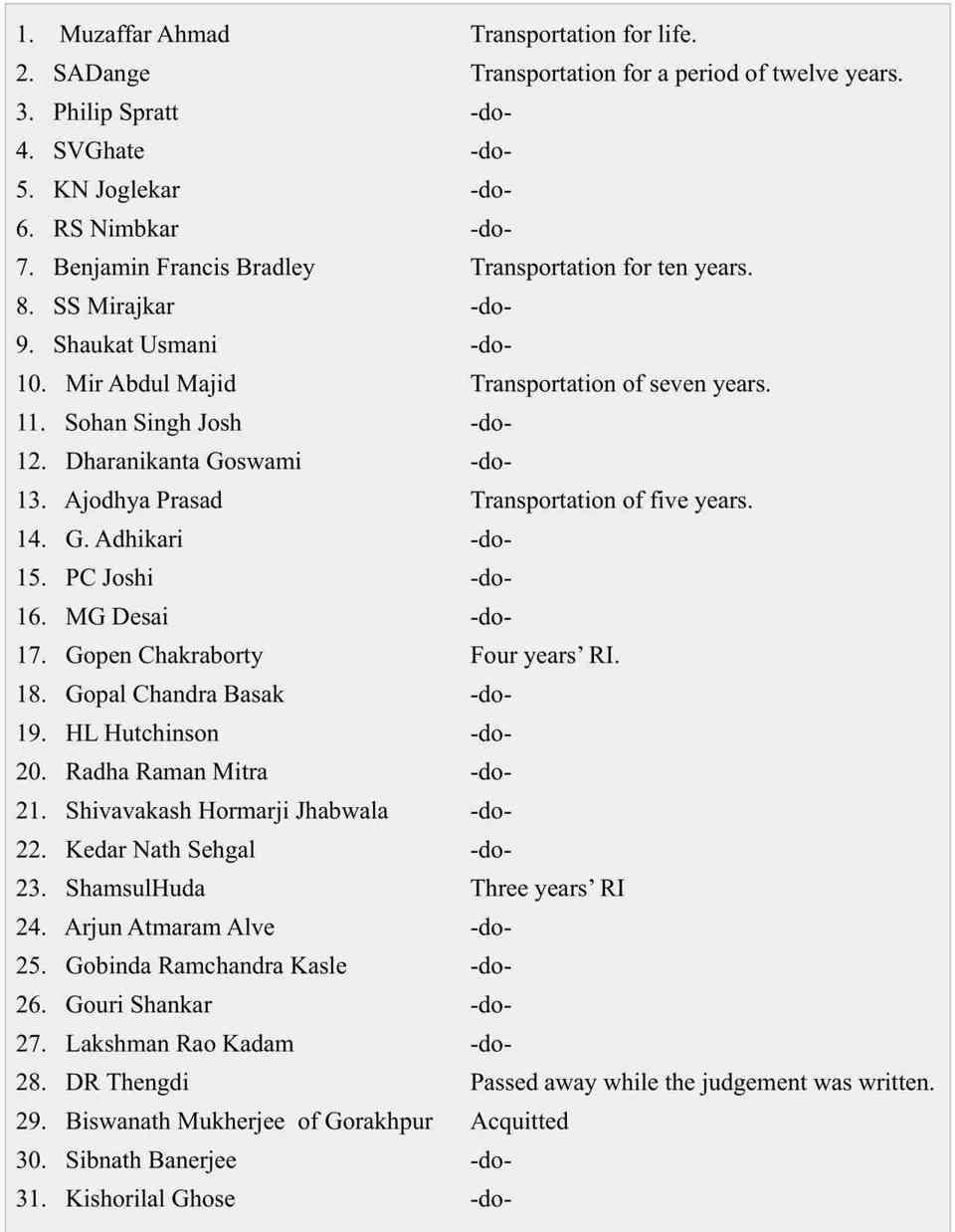

The attack was planned at the highest level. A secret telegram from Governor-general Irwin to Home Secretary for India in London states, “Indian political situation had appreciably taken a leftward shift and we apprehend a large-scale disturbance in near future.” (Secret Tel. No. 2555,19 January F/N. No. 184/29, India Office Library, London, quoted and translated from Goutam Chattopadhya's Peshawar to Meerut, op. cit., p 75.). So, on 20 March, 1929 the sweeping round-up of 31 labour leaders (see list below) from Calcutta, Bombay, UP and Punjab took place. And they were brought to Meerut for the Meerut Conspiracy Case. Three Englishmen, Bradley, Philip Spratt and Lester Hutchinson who were active in the working class movement and as many as eight members of the AICC were among the arrested. In comprehensive search operations throughout the country, a good deal of published and unpublished documents, letters, magazines, leaflets etc. were seized and presented as evidence along with intercepted correspondence. Meerut was chosen for the conspiracy trial since the British “could not ... take the chance of submitting the case to the Jury.” (Home member HG Haig, confidential note, 20 February ’29).

But this time the British aim proved counter-productive at least in one respect. Whereas Kanpur, the venue of the previous anti-communist trial, had become the birth place of the CPI, Meerut became a spectacular platform for communist propaganda. The accused communists were better organised to make use of the court room for the spread of the communist ideology, their programmes, amis and objectives. The British move to drive a wedge between communists and nationalist leaders also proved futile. Nehru, Gandhi and many others visited the Meerut jail while the accused communists also sent messages to the satyagrahis in different jails supporting their just struggles for political status. The accused communists also tried to shift the case to one of the metropolitan cities but this appeal was turned down by the sessions court. Also their attempt to utilise the witnesses from abroad and the arrangement of a lawyerfrbm England by the National Meerut Prisoners’ Defence Committee for the defence of the case and the help of comrade JR Campbell of CPGB as political adviser were turned down by the British government. The conspiracy trial under section 121 A of the Indian Penal Code (offences involving treason) was proceeded in the Meerut Sessions Court of RL Yorke. Two Defence lawyers, KF Nariman and MC Chagla appeared on behalf of the accused. Beside giving individual statements in their defence, a general statement of 18 communist accused was given during the magistrate and sessions court trials. This general statement vigorously exposed the bankruptcy and hypocrisy of the British rule in India and their ‘civilised’ legal system and put forward the communist programme and policies (See Text VI25 for short excerpts.) After four long years of sham trial, the verdict was given on 16 Jan. 1933. This was as follows:

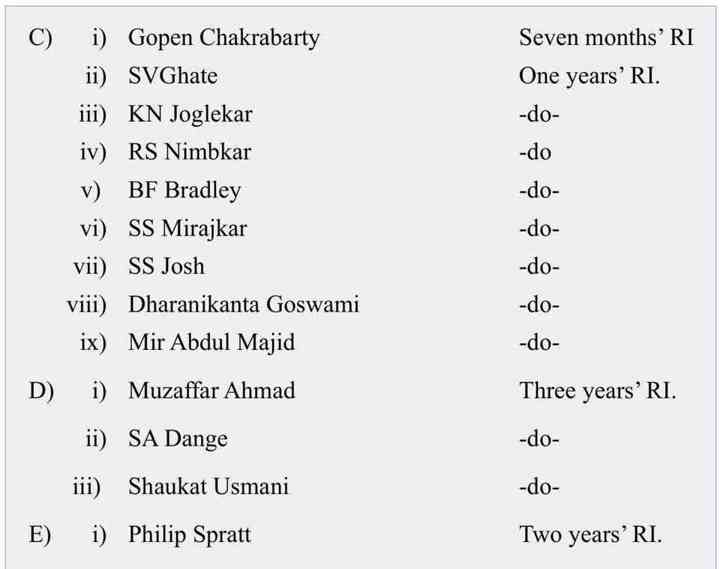

After the sessions trial was over, the accused communists appealed to the High Court. In the High court, Dr. Kailas Nath Katju and two junior advocates, Shyam Kumari Nehru, and Ranjit Sitaram Pandit appeared as defence lawyers. After eight working days of sitting, the High Court judge delivered their judgement as follows:

A) 1. MG Desai, 2. HL Hutchinson, 3. SH Jhabwala, 4. Radha Raman Mitra, 5. Kedarnath Sehgal, 6. Gobinda Kasle, 7. Gouri Shankar, 8. Laksman Rao Kadam, 9. Arjun Atmaram Alve — All acquitted.

B) 1. Ajodhya Prasad, 2. PC Joshi, 3. Gopal Basak,

4. Dr. G Adhikari, 5. Shamsul Huda — the court upheld the sentences under 121A of the IPC by the sessions court, but due to punishment already received, they were all released.

“The sentences were reduced later (by the High Court) under pressure of the British Trade Union Congress and others” wrote Prof. Michael Brecher of Canada (Nehru : A political Biography, p 136). Not only did workers all over the world launch agitations against the trial and conviction, even men like Ro.main Rolland and Prof. Albert Einstein raised their voices in protest against the case. Harold Laski wrote:

- “The Meerut trial belongs to the class of cases of which the Mooney trial and the Sacco-Vangetti trial in America, the Dreyfus trial in France, the Reichstag fire trial in Germany, are the supreme instances.”[1]

The Meerut trial[2] projected the communists as the foremost fighters for freedom who bore the brunt of imperialist attack. This earned them truly national support — even men like Gandhi felt compelled to voice their sympathy and respect. But the CPI failed to reap any harvest; for in the first place, the internment of practically all leaders, precisely at the moment when the Party was planning to consolidate itself, made any national-level planning and work impossible. Secondly, the new leadership that gradually emerged from the grassroots proved to be more loyal than the King in following the new Comintern line, which in its turn shifted more to the left just after the Sixth World Congress. The story of this new period we will now study in Part IV of the volume.

Notes:

1. H. Laski’s “Preface” to Hutchinson’s Conspiracy at Meerut, p 8.

2. A large number of books with details on this case are easily available, such as : The Great Attack by Sohan Singh Josh, PBH (New Delhi,1979); Meerut Conspiracy Case and The Left Wing in India by Pramita Ghosh, Paoyrus (Calcutta, 1978). So we limit ourselves to a brief general comment.