1980-81 Agricultural Census : The Case of Bihar

IN Bihar the 1980-81 Agricultural Census was conducted on a complete enumeration basis by retabulation of data from land records. For the purpose of this Census, the operational holdings

What It Reveals

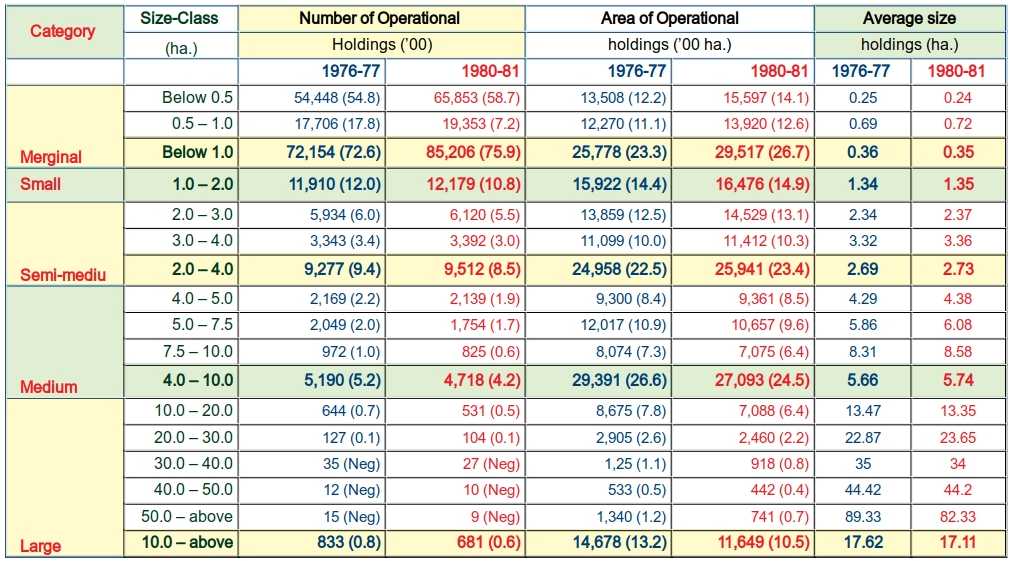

As the figures in the accompanying table show, during 1980-81, marginal holdings accounted for 75.9 per cent of all holdings and 26.7 per cent of the total area under these holdings, while large holdings, accounting for a meagre 0.6 per cent of all holdings, occupied no less than 10.5 per cent of the total area. The corresponding figures for small, semi-medium and medium holdings are : 10.8 and 26.7; 8.5 and 23.4; and 4.2 and 24.5.

Compared to the 1976-77 figures, the share of marginal holdings has gone up by 3.3 and 3.4 percentage points in terms of number and area respectively, while that for large holdings has fallen by 0.2 and 2.7 percentage points. The number of small and semi-medium holdings fell by 1.2 and 0.9 percentage points while their shares in area went up by 0.5 and 0.9 percentage points respectively. And medium holdings found their share depleting by 1 per cent in terms of number and by 2.1 per cent in terms of area.

As a whole, the distribution is still highly skewed. Whatever slight variations in percentage are discernible are attributed by the government to its measures of land reforms, particularly the enforcement of ceiling laws.

And What It Conceals

Well, let us leave the Census report for a while and consider some unofficial informations. One need not sift through voluminous research works to gather these informations, even general newspapers frequently carry these reports. Take the case of Purnea district for example. The evolution and unabated predominance of big landlordism in this district is a topic that comes up in almost any discussion of the rural reality in Bihar. Consider the case-study of Purnea by Manoshi Mitra and T Vijayendra (Agrarian Movements, pp 88-118 ). Citing the reference of Francis Buchanan (An Account of the District of Purnea, 1928), the authors tell you how in the late nineteenth and the twentieth century, the one-time under-renters of the zamindars (officials appointed by them to supervise the rents as well as to deal with rent-farmers and disputes with the government) “emerged as considerable landlords themselves” and came to establish their notoriety as being “among the most oppressive”. “Among them are such people as Babu Moulchand, Raghubans Narayan Singh of Kursela and others, under-tenure holders of the Darbhanga Raj, who are reported to be among the largest landholders in India today according to the Government of Bihar”, inform the authors (Ibid, p 92).

Number, Area and Average Size of Operational Holdings in Bihar in 1976-77 and 1980-81

Note : Figures in brackets indicate percentages on total of the corresponding column,

Source : Agriculural Situation in India, August, 1984

Now open The Telegraph of 25 January, 1986, and you will find that their successors have not only not lost their control over the enormous landed wealth handed down over generations, but have further entrenched themselves in various positions of power and privilege in the new state structure :

Dinesh Kumar Singh (of the erstwhile Kursela state), a proud thakur, and still as big a landlord as ever, is minister for food and supplies in the Congress government of Bindeswari Dubey currently ruling Bihar. Sarju Mishra, the health minister is confidently said to control nearly a thousand acres in Purnea. Sir Narayan Chand is perhaps the biggest of them all, controlling perhaps as much as 5,000 acres in Purnea. He is also the father of Madhuri Singh, an honourable member of Parliament elected on the Congress ticket. ( M. J. Akbar, Dateline ).

True, not all old zamindars could retain their land and power, but then their place has been occupied by new entrants from among the traders and contractors and even doctors and lawyers, who have purchased zamindari interests to emerge as medium to big landholders.

Sahu Parbatta is such a case in Purnea. He evicted tenants, engaged under-tenants, paid rent to the zamindars and still had a surplus. He used the capital to buy land and today he is supposed to have some 30,000 acres. (Mitra and Vijayendra, Agrarian Movements, p 98).

In all, there are believed to be 41 exceptionally big landlords each owning no less than 1,000 acres of land in Purnea.

West Cbamparan is another district notorious for big landlordism. Here are the foremost landlords in the district— Betia Raj : 20,000 acres, Faiz Alam : 15,000 acres, Baidya Nath Chauhan : 15,000 acres, Kapil Kumar : 10,000 acres, Raja of Ramnagar : 10,000 acres, D. K. Sikarpur : 9,000 acres, Islam Sheikh : 8,000 acres, Joy Narayan Marwari: 6,000 acres, Dumania estate : 6,000 acres. Many from these families are MPs or ministers and MLAs of Bihar. To have an idea of their overall wealth and power, take a close look at the Dumania estate, for instance. The family has a farm of 6,000 acres and rents out dwelling-houses and market-places. These apart, it owns 20 tractors and a tractor agency, a cinema hall, one hotel and a lodge, poultry farms, pig-breeding farms, dairy farms, mango and vegetable trade, and so on and so forth. In addition to daily workers they have 500 salaried employees. For different jobs they have different managements and the entire property is managed under a cooperative banner.

Coming to the district of Gaya, the notorious Mahant of Bodh Gaya controls 18,000 acres of land, of which nearly 5,000 acres are located in Bodh Gaya and the rest in other places of Bihar and Madhya Pradesh. Among the other major landowners in Gaya are Satyendra Narain Singh, an erstwhile leader of the Janata Party and now a Congress(I) MP, who owns 4,300 acres; Anjar Hussain with 3,650 acres; and Dr. Bijoy Singh, MLA and nephew of Satyendra Narain Singh. with 700 acres.

These three districts apart, the districts of Rohtas, Palamau and Bhagalpur are also notorious for big landlordism. But looked through the glasses of government census, this face of rural Bihar stands perpetually concealed.

The Trick : Semi-feudalism Glorified

So, unofficial consensus and official census seem to be at loggerheads. The trick lies essentially in the very mode of the census operation, in the very category of "operational holdings" as separated from the question of ownership and actual control.

Thus, when big holdings are rented out in small parcels to a huge number of tenants, or when large landowning families, splitting formally into several smaller units, resort to holding land in all sorts of fictitious names (cooperatives, farms, orchards and what not) so as to avoid the ceiling laws — all these are counted in census records as so many operational holdings belonging to this or that size-class. No wonder then, that the census data will show a continuing increase in the number of, and area under, small and marginal holdings at the expense of a corresponding decrease in the number of, and area under, medium and large holdings. And it goes without saying that a good majority of those who operate these small and marginal holdings are actually tenants-at-will, cultivating under onerous, semi-feudal conditions. The survivals of feudalism are thus glorified as the outcome of progressive land reforms!