Operation SAP II: Grave New World

HAVING ALREADY carried out or at least firmly initiated the core of the structural adjustment programme, namely, devaluation and partial convertibility of the rupee, removal of almost all checks on imports, freedom for private domestic and foreign capital to enter and expand in every sphere of the national economy, reduction ('rationalisation') of taxes for the wealthier sections and legitimatization of all their speculative and black income, and lowering fiscal deficit by slashing the quantum of subsidies and public investment and the degree of state's intervention in the economy – the government and its Fund-Bank consultants are now shifting their focus to the following issues which are likely to prove much more contentious than the above reforms.

Exit Policy: Ostensibly, the idea is to facilitate free closing down of all 'non-viable' industries and enhance the mobility of capital. But as in the case of all black laws which are enacted with a selective scope and then gradually generalised, the exit policy is also bound to be used in a sweeping way against workers in all branches of production. For, as a World Bank paper on “Regulation of Labour and Labour Relations” puts it, the essential argument is that the stagnation in employment growth in India is because of 'excessive labour protection' and that to overcome it, the 'highly privileged' organised labour should be subjected to 'competition' from the millions of unorganised workers.

In all likelihood, the government will try to realise the exit policy through a series of amendments to various existing labour-related laws. Among the salient recommendations made by an Inter-ministerial Working Group on Industrial Restructuring are:

(a) abolition of Sections 522 to 527 of the Companies Act to rationalise the liquidation and winding up proceedings of a company,

(b) setting up of registered auction and debt realisation centres around the country to speed up the process of liquidation of sick units,

(c) empowering the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (Board for Industrial Funeral Rites!) to issue final orders for liquidation of companies without reference to any higher court, and

(d) investing employers with much greater authority to retrench or lay workers off.

Already, the Sick Industrial Companies Act has been amended to extend the purview of the BIFR to sick public sector units as well. As many as 58 sick PSUs have already been referred to the BIFR and 47 of them are reportedly marked for closure. A National Renewal fund has also been launched with World Bank assistance, ostensibly to provide a measure of economic security and redeployment facilities to the affected workforce.

Privatisation: In India, this phenomenon is unlikely to proceed in the straightforward manner it has happened in Britain or nearer home in Pakistan. What we are witnessing here is a kind of gradual and backdoor privatisation: selling of public sector shares to private hands, converting public sector units into joint sector by allowing massive private and foreign equity participation – to the extent of 49% and even 51% in some cases, farming out or sub-contracting public sector production and services increasingly to private hands and so on. Also by encouraging private sector entry into areas reserved earlier for the state sector the relative importance of the latter has been subjected to a steady erosion.

To reform the banking and insurance sector, the government has already come up with the Narsimham Committee report. Instead of direct denationalisation of public sector banks, the government seems to be opting for an indirect way. The gameplan is that private and foreign banks will be allowed to freely expand their operations and the proportion of priority sector lending by public sector banks will be progressively brought down to as low as 10%. The subversion of the priorities and objectives of public sector banks will thus be complete even without formal denationalisation.

Curbs on TU Rights: Efforts are on to curb trade union rights by amending acts like the Industrial Disputes Act and Trade Unions Act and emasculate and sanitise the trade union movement by limiting the number of trade unions in every industry and raising the requisite membership strength for awarding registration to new trade unions and derecognising the struggling unions wherever possible. In his Republic Day speech this year the President called fora two-year 'voluntary' embargo on strikes and lock-outs.

Incidentally, even without any explicit general ban on strikes and other militant forms of trade union struggle, the government and big capitalists have been quite effective in enforcing industrial 'peace' on the workers. A recent study of industrial conflicts in the country shows that in 1990, the incidence of industrial disputes, workers involved and mandays lost were only 40%, 50% and 61% respectively of the 1970 level. More strikingly in the 80s the number of mandays lost due to lockouts has overtaken that due to strikes, indicating the employers' aggressive bid to cow down workers with threats of closure.

De-subsidisation and marketisation : The World Bank has long been pressing for a drastic reduction in subsidies so that prices of all goods and services, essential and luxury alike, are determined 'freely' at the market through an unregulated interaction of the forces of demand and supply. The 1992-93 Central Budget and various State Budgets have already gone a long way towards accommodating this cardinal Fund-Bank principle. Railway and bus fares, electricity rates, milk prices, educational fees, all have been revised upward. The University Grants (Graves?) Commission has asked the universities and colleges to generate their own resources for even paying dearness allowances to teachers and funding basic facilities for the educational community. Proposals ordering fresh hikes in petrol and diesel prices and scrapping food subsidy for the urban middle class are reportedly awaiting the government's green signal. And the list is endless. ...

Budget 1992 : The SAP Strap

IF last year's budget had announced the launching of the notorious Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) under the Fund-Bank tutelage, Budget '92 only tightened the SAP strap around the nation's neck. The rupee was devalued once again, this time through the backdoor, as the budget declared 60% of all foreign currency inflow convertible in the open market. The inflationary toll has already begun with the prices of all imported inputs skyrocketing. Also stoking the inflationary fire were steep hikes in excise duties of almost all essential commodities.

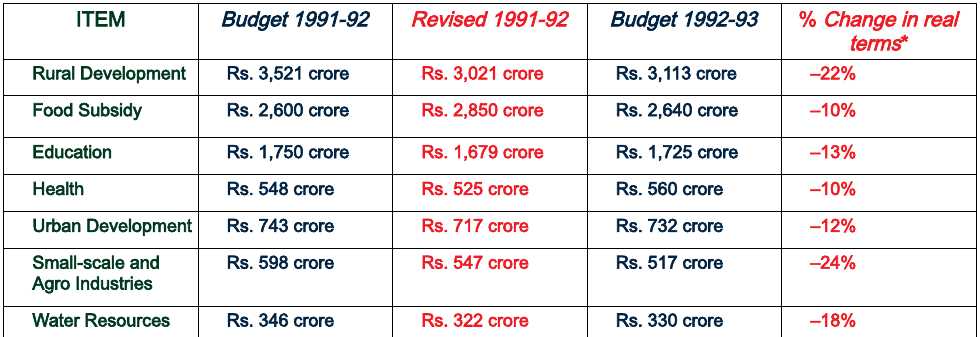

Keeping in tune with IMF diktat to reduce the overall fiscal deficit, Budget '92 has complied fully with the brunt of both expenditure cuts and revenue mobilisation borne entirely by the poorer sections. So while concessions are heaped upon the rich with cuts in wealth tax, expenditure tax and even income tax in the higher brackets, the common man is left to contend with a slash in food subsidies as well as health, education and rural welfare spending (see table).

The budget also revealed its skewed priorities by announcing wideranging reduction in custom duties and all sorts of red carpet schemes to coax smugglers, hawala traders, and tax evaders of all shades to part 'legally' with money made illegally. The gold bond scheme introduced for converting black money into gold with no questions asked is an incentive only to tax evaders who are delighted to have a government that whitewashes their crimes instead of punishing them.

* = comparison between Budget estimates of 1991-92 on the basis of 12% inflation rate