Agricultural Labourers

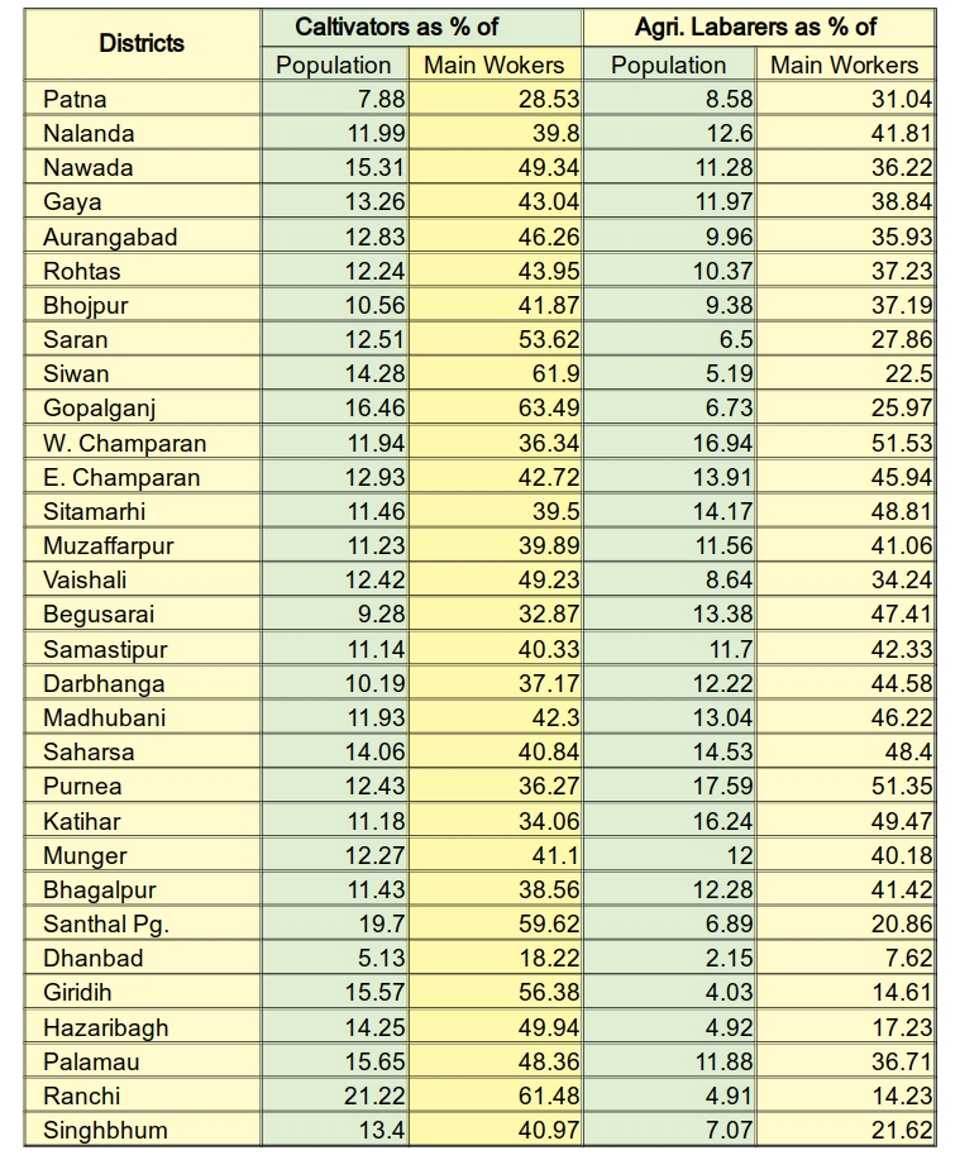

THEIR number has greatly increased since the 60s, parti, cularly as a result of the large-scale eviction of erstwhile tenants in the wake of the ceiling act. In 1981, they accounted for 35.50 per cent of the total population of main of workers in Bihar while for India as a whole the corresponding share was only 24.94 per cent. Regionwise, the percentage share was highest in North Bihar, followed by South Bihar and Chhotanagpur in that order. Districtwise, the percentage was highest in West Champaran (51.53), followed by Purnea (51.35) and Katihar (49.47). In Chhotanagpur, the figure was highest in Palamau (36.71 per cent), nearly double the average for the region (See accompanying table )

Low figures for agricultural labourers in the Chhotanagpur region are due to the existence of hilly tracts, prevalence of adivasi population, and the consequent special tenurial systems. However, large numbers of adivasis have migrated to the tea gardens of Assam and to North Bihar as labourers. During the cultivating seasons, one also finds them migrating to West Bengal, and nowadays to Punjab, too, in search of work as agricultural labourers.

In caste terms, the agricultural labourers of Bihar have the following percentage distribution — Upper Castes : 0.3; Middle Castes : 34.2; Scheduled Castes : 39.1; Scheduled Tribes : 12.4; Muslims : 14.0 (S. R. Bose and P P Ghosh, Agro-Economic Survey of Bihar).

Districtwise Distribution of Cultivators and Agricultural Labourers as Percentages of Total Population and Total Main Workers (1981 Census)

Source : Compiled from 1981 Census Abstract.

Agricultural labourers in Bihar can be broadly classified into the following three categories :

(a) Banihars or Charwahas : They are actually attached labourers, working in the landlords’ fields on an annual contract basis. They are allotted little pieces of land, varying in size from 5 kathas to 1 bigha

(b) Land-owning Labourers : Although they own small pieces of land, for their subsistence they are forced to rely mostly on their work as wage labourers.

(c) Landless Labourers : Their number is not quite high and they are heavily underemployed. Recent years have witnessed a tremendous increase in their migration to Punjab where the wages are quite high in comparison to Bihar. In Bihar, their daily wages range from 750 grams to 2 kgs. of wheat or rice, or Rs. 2 to Rs. 10 in cash. During harvesting season, they receive one out of every 10 bundles of crops harvested as wages. The wages differ greatly in different areas and in different operations depending upon a number of factors, the foremost of which is the state of their organised strength.

Full-time free wage labourers working in modern capitalist farms or in areas of cash crops are quite an exception in Bihar.

The struggles of agricultural labourers revolve around the issues of wages; dwelling land ; interest rates; communal, government, surplus and benami lands under the occupation of landlords and rich peasants; water resources; fishing; social oppression and so on and so forth. Moreover, in Bihar, unemployment, not to speak of underemployment, is widespread among agricultural labourers and they have no avenues open to them for moving to industrial centres. Apart from the struggle for rise in wages, one also finds agricultural labourers quite eagerly participating in struggles for land, both for the purpose of dwelling as well as self-cultivation. Even if sometimes they managed to get parchas from the government officials, the land remained under the illegal control of gun-totting landlords. Any protest on their part is met with immediate attacks by the landlords. With their hamlets surrounded and set ablaze, property looted, women raped, and dear and near ones killed by the merciless landlords and their merceuaries, dissenting agricultural labourers are either forced to surrender or made to flee the village.

It is this situation that is being challenged today by the agricultural labourers of Bihar, under the leadership of the communist revolutionaries and with the aid of their own armed squads. Not only the agricultural labourers, but the poor and lower-middle peasants and the half-labourer-half-tenants are also there in the forefront of the struggle, and in this they enjoy the support of sizeable sections of the middle peasants, too. And the targets are the landlords and those kulaks who have virtually declared a war on the rural poor.

The pages that follow will bring you the saga of this heroic struggle. Over, then, to the flaming fields of Bihar.