A Profile of Some of The 1857 Revolutionaries

Veer Kunwar Singh

Kunwar Singh was born in Jagdispur of the Shahabad (now Bhojpur) District of Bihar to a landed family. Remarkably, he led the armed uprising of 1857 at the age of 80, not caring for his failing health. Oral history maintains that he said he had been waiting for the uprising, and was sorry only that it had come when he was so old. He was an expert in guerilla warfare, baffling the British forces with his military tactics and expelling them from Shahabad on 23 April 1858. He died a few days after – but only after having routed the East India Company troops.

Bhojpuri folk songs commemorate him thus:

Ab chhod re firangiya hamar deswa ! Lutpat kaile tuhun, majwa udaile kailas, des par julum jor. sahar gaon luti, phunki, dihiat firangiya, suni suni Kunwar ke hridaya me lagal agiya! Ab chhod re firangiya hamar deswa!

(Now quit our country oh Britisher! For you have looted us, enjoyed the luxuries of our country and oppressed our countrymen. You have looted, destroyed and burnt our cities and villages. Kunwar’s heart burns to know all this. Now quit our country oh Britisher!)

Kunwar Singh’s correspondence with 1857 leader from Jehanabad Qazi Zulfikar Ali show clearly that they were comrades and the best of friends. In these letters dated 1856 they discuss plans to march to Meerut – even before the uprising broke out in 1857. In the letters, they plan to divide the freedom fighters’ army into two wings, one under the command of Kunwar Singh while the other under Zulfiqar’s command. (https://www.heritagetimes.in/in-1856-babu-kunwar-singh-)

On 23 April 2022 however, Home Minister Amit Shah attended an event organised by the BJP at Jagdishpur, with the clear intention of pushing a communal rather than an anti-colonial narrative. The same BJP is erecting a statue of 1857 traitor Dumraon Maharaj to whom the British gave a large portion of Babu Kunwar Singh’s property as a reward after the latter’s death! BJP cannot claim to revere both traitors and martyrs of the freedom struggle: both Dumraon Maharaj and Kunwar Singh; both Godse and Gandhi!

Ironically, on the same day that Amit Shah was garlanding a statue of Kunwar Singh, the district administration had locked Kunwar Singh’s grand daughter-in-law into her home to prevent her being able to raise the issue of the police and administration’s complicity in the cover-up of the recent murder of Kunwar Singh’s great grandson Bablu Singh.

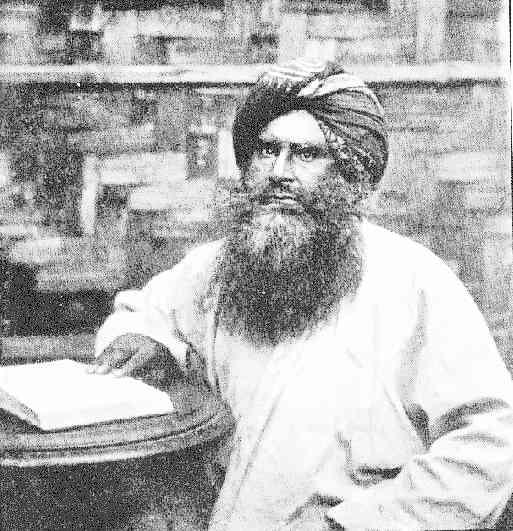

Maulvi Ahmadullah Shah

Maulvi Ahmadullah of Faizabad was an outstanding leader of the 1857 uprising. British officer Thomas Seaton described him as “A man of great abilities, of undaunted courage, of stern determination, and by far the best soldier among the rebels.” G. B. Malleson, another British officer who wrote a history of the 1857 uprising, wrote that “The Maulvi was a remarkable person. His name was Ahmadullah and his native place was Faizabad in Oudh. In person, he was tall, lean and muscular, with large deep eyes, beetle brows, a high aquiline nose, and lantern jaws. It is beyond doubt that behind the conspiracy of 1857 revolt, the Maulvi’s brain and efforts were significant. Distribution of bread during the campaigns, Chapati Movement, was actually his brainchild.”

Maulvi Ahmadullah of Faizabad was an outstanding leader of the 1857 uprising. British officer Thomas Seaton described him as “A man of great abilities, of undaunted courage, of stern determination, and by far the best soldier among the rebels.” G. B. Malleson, another British officer who wrote a history of the 1857 uprising, wrote that “The Maulvi was a remarkable person. His name was Ahmadullah and his native place was Faizabad in Oudh. In person, he was tall, lean and muscular, with large deep eyes, beetle brows, a high aquiline nose, and lantern jaws. It is beyond doubt that behind the conspiracy of 1857 revolt, the Maulvi’s brain and efforts were significant. Distribution of bread during the campaigns, Chapati Movement, was actually his brainchild.”

Malleson paid this tribute to the Maulvi Ahmadullah on recording his death in battle: “If a patriot is a man who plots and fights for independence, wrongfully destroyed, for his native country, then most certainly, the Maulvi was a true patriot.”

It is fitting that in Ayodhya where the RSS and BJP fascists demolished the 16th century Babri Masjid, the five acres of land allotted by the Supreme Court to the Muslims is being used to build a complex named after Maulvi Ahmadullah Shah Faizabadi, comprising a mosque, hospital, museum, research centre and community kitchen for the poor. The Muslims have wisely chosen to answer an act of hate and a verdict that benefited the hateful and violent aggressor with a decision to create structures that will serve all the people of Faizabad and Ayodhya, and honour the memory of the first war of independence in which Muslims and Hindus unitedly laid the foundations of India.

The Adivasis of Chhotanagpur

Historian Shashank Sinha notes that “While the creation of a new district of Santhal Parganas (after the brutal suppression of the Santhal Hul or rebellion of 1855–56) did give some respite to the Santhals of the immediate region, their brethren in Hazaribagh and Manbhum (which also formed a part of the Hul) did not get any ameliorative benefits.” As a result the Santhals in these regions joined the 1857 uprising to settle accounts with moneylenders, and acted jointly with the soldiers to attack feudal forces who were collaborators of the British.

Sinha notes that “The Santhals continued their activities even after the defeat of the sepoys at the Battle of Chatra. Around 10,000 people burnt a thana (police station), looted Esmea Chatti (at Hazaribagh) and attempted to cut off communications between Hazaribagh and Ranchi.14 Later, a group plundered Gomea and burnt government build- ings and records. Like the Santhals, the dispossessed Bhuiya Tikaits, in the north of Hazaribagh district, saw in the 1857 disturbances an opportunity to recover their lands from old purchasers.”

Sinha cautions: “In areas such as Hazaribagh, Singhbhum and Palamau where tribals participated, they defied stereotypical imagings. Besides being mobile, one witnesses adivasis uniting with non-adi- vasis and regional elites to fight against their local enemies and/or imperialist forces.”

(‘1857 and the adivasis of Chotanagpur’, Shashank S Sinha, The Great Rebellion, pp 16-31)

1857 in Andhra Pradesh

(Excerpted from the chapter by B. Rama Chandra Reddy in The Great Rebellion).

It is often mistakenly assumed that the 1857 uprising was confined to North India. In fact, the fire spread all the way to Southern India.

Reddy notes that “The immediate precursor to the Great Uprising was a mutiny on 28 February 1857 of the ‘native’ sepoys of Vizianagaram belonging to the First Regiment ‘native’ Infantry.”

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

On 17 July 1857, two rebels, Turabaz Khan and Moulvi Allauddin, led an attack on the British residency at Hyderabad. They were supported by a ‘crowd’ of 5,000 people, including the Rohillas and the civil population. Then again, about a month later in Cuddapah, on 28 August 1857, one Sheik Peer Shah tried to ‘incite’ the ‘native’ officers and men of the 30th Regiment ‘native’ Infantry.

Korukonda Subba Reddy, who belonged to the Konda Reddy tribe and was the hill chief of Koratur village situated on the banks of the River Godavari led a protracted guerilla war, forcing the British troops to follow them into the malaria-prone hill regions. On 7 October 1858, the tribal rebel leaders Korukonda Subba Reddy and Korla Setharamaiah were finally hanged at the village of Buttaya Gudem. Korla Venkata Subba Reddy and Guruguntla Kommi Reddy suffered a similar fate at the village of Polavaram; and Korukonda Tummi Reddy was hanged at Tudigunta.

According to oral tradition, the dead body of Korukonda Subba Reddy was kept on display in an iron cage, later termed the ‘Subba Reddy Sanchi’ (bag), and was left hanging for a long time by the British for public viewing in order to create terror in the people’s minds about the fate of a rebel.

Uprisings were also seen in the Gudem tribal area (Vizagapatnam district).

Azeezun Bai

(The sections on Azeezun Bai and Begum Hazrat Mahal are excerpted from the chapter by Lata Singh in The Great Rebellion).

Most of the accounts mention how Azeezun used to be on horseback in male attire decorated with medals, armed with a brace of pistols as she joined the Rebellion.

Azeezun lived in the Lurkee Mahil, in Oomrao Begum’s house in Kanpur. Her mother was a courtesan in Lucknow. Azeezun’s mother died when she was very young and she was brought up by a courtesan in Lucknow.So Azeezun must have left the city of Lucknow and settled in Kanpur. ...one of the probable reasons for Azeezun going to Kanpur may have been her strong passion for independence. She probably did not want to stay under someone’s patronage, being the kind of person that she was, as is reflected in her role in the 1857 Rebellion.

Azeezun lived in the Lurkee Mahil, in Oomrao Begum’s house in Kanpur. Her mother was a courtesan in Lucknow. Azeezun’s mother died when she was very young and she was brought up by a courtesan in Lucknow.So Azeezun must have left the city of Lucknow and settled in Kanpur. ...one of the probable reasons for Azeezun going to Kanpur may have been her strong passion for independence. She probably did not want to stay under someone’s patronage, being the kind of person that she was, as is reflected in her role in the 1857 Rebellion.

Azeezun was very close to the sepoys of the 2nd Cavalry, who visited her house. She was particularly close to the sepoy Shamsuddin Khan of the 2nd Cavalry. Shamsuddin played a very active role in the 1857 Rebellion in Kanpur. Meetings of rebels would take place in his house to work out plans for the Rebellion. Shamsuddin visited Azeezun frequently.

Besides the fact that Azeezun, who had been known to both Nana Sahib and Azimullah Khan, and whose house had been the meeting point of sepoys, she was looked upon as one of the key conspirators in the 1857 Rebellion. It seems that she was aware that the Rebellion in Kanpur was planned for 4 June 1857. Her role is seen as that of informer and messenger. Some accounts also mention that Azeezun had formed a group of women, who fearlessly went around cheering the men in arms, attending to their wounds and distributing arms and ammunition.

According to Nanak Chand, ‘it shows great daring in Azeezun that she is always armed and present in the batteries owing to her attachment to the cavalry, and she takes her favourites among them aside and entertains them with milk etc. on the public road’. Another eyewitness wrote that ‘it was always possible to see her, armed with pistols in spite of the heavy fire, in the battery, amongst her friends, the cavalrymen of the 2nd regiment, for whom she cooked and sang’.

Although this chapter discusses the role of Azeezun in the 1857 Rebellion, there are bound to be hundreds of stories about the role of these women in the Rebellion, but most of them seem to have gone unrecorded. There are unsubstantiated accounts of girls taking to the streets in a battle with British soldiers. Kothas (houses of courtesans) became centres of conspiracy, and many of these women joined in the Rebellion of 1857. Their role is documented as covert but generous financiers of the action. These women, although patently non-combatants, were penalized for their alleged instigation of and pecuniary assistance to the rebels. The British officials were aware that their kothas were meeting points for the rebels, which were looked upon with suspicion as places of political conspiracy. In fact, their role in the Rebellion can best be judged from the ferocity of the British retribution that was directed against them. There was large-scale appropriation of their property. In Lucknow, the centre of courtesans, the British, after quelling the Rebellion of 1857, had turned their fury against the powerful elite. Their names were on the lists of property confiscated by British officials for their proven involvement in the siege and the Rebellion against colonial rule in 1857.

Begum Hazrat Mahal

Begum Hazrat Mahal emerged as an important political figures who began her profession as a courtesan. She married the Awadh Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, and when the latter was exiled, she agreed to the suggestion by the freedom fighters that she crown her minor son Birjis Qadr and name herself as regent. Interestingly, the other Begums were approached before her, but none agreed to crown their sons as king, fearing the repercussions of such an action. After a long siege, Lucknow was recaptured by the British, forcing Hazrat Mahal to retreat in 1858. She refused to accept any kind of favours and allowances offered by the British rulers. She spent the remaining years of her life in Nepal.

Begum Hazrat Mahal emerged as an important political figures who began her profession as a courtesan. She married the Awadh Nawab Wajid Ali Shah, and when the latter was exiled, she agreed to the suggestion by the freedom fighters that she crown her minor son Birjis Qadr and name herself as regent. Interestingly, the other Begums were approached before her, but none agreed to crown their sons as king, fearing the repercussions of such an action. After a long siege, Lucknow was recaptured by the British, forcing Hazrat Mahal to retreat in 1858. She refused to accept any kind of favours and allowances offered by the British rulers. She spent the remaining years of her life in Nepal.

1857 in Tamil Nadu

(Excerpted from ‘Upsurge In South’, N Rajendran, Frontline, June 2007)

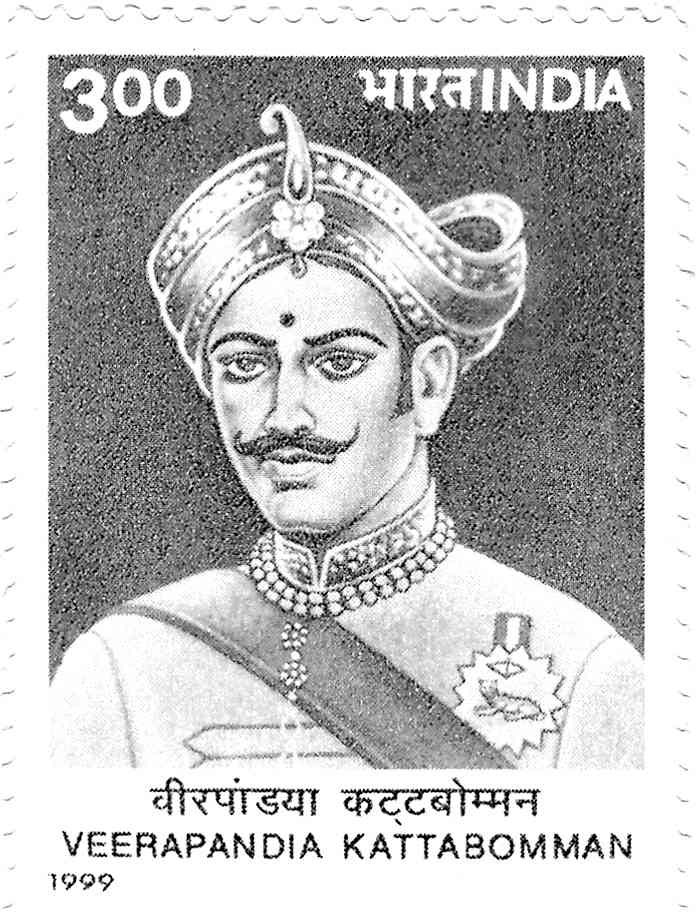

In what is now Tamil Nadu, as in other parts of India, the earliest expressions of opposition to British rule took the form of localised rebellions and uprisings. Chief among these was the revolt of the Palayakkarars (Poligars) against the East India Company. The notable Poligars who raised the banner of revolt deep south in the Madras Presidency were Puli Thevar, Veera Pandiya Kattabomman and the Marudu brothers of Sivaganga. There were two major campaigns undertaken by the British against the Poligars in the late 18th century.

Ghulam Ghouse and Sheikh Mannu, two activists, were arrested in February 1858 for pasting wall posters “of a highly treasonable character”, that is, in favour of the 1857 Revolt, and urging the people of Madras to rise against the British.

Coastal regions such as Madras and Chingleput (Chengelpet) and interior areas such as Coimbatore were considered “disturbed” during the 1857 Revolt, according to reports of the period. In Thanjavur in southern Tamil Nadu, a revolutionary by name Sheikh Ibraham was apprehended in March 1858 and convicted on charges of sedition.

Similarly, in North Arcot, in anticipation of the Revolt of 1857, plans and secret meetings were held for organising a war against the British, from as early as January 1857. It is on record that one Syed Kussa Mahomed Augurzah Hussain held talks in this connection with the zamindars of Punganur (in Chittoor district, now in Andhra Pradesh) and Vellore. Syed Kussa was apprehended by the British in March 1857 and a security was demanded of him.

In 1857, the 18th Regiment of the British army was quartered at Vellore. Some sepoys of the Regiment revolted in November 1858. In the armed struggle, Captain Hart and Jailor Stafford were killed. The Sessions Judge of Chittoor tried a sepoy of the Regiment on charges of wilful killing and sentenced him to death.

In Salem, the news of the start of the 1857 Revolt was met with much commotion as it was rumoured that the patriotic army would march to the area soon. On the evening of Saturday, August 1, 1857, a crowd consisting of a large number of weavers assembled on Putnul Street near the house of one Ayyam Permala Chary, saying that the Indian soldiers would be coming and that the British flag would fall. Hyder, a thana peon, told the assembled people that “about this time of the day, a flag (of India) will have been hoisted at Madras”.

During the revolt, a sanyasi called Mulbagalu Swamy in Bhavani, an industrial town near Coimbatore, started preaching that British rule should be brought to an end. “Let all the Europeans be destroyed and the rule of Nanasahib Peshwa prevail,” he would tell his devotees during his daily puja. He was finally apprehended at Bhavani by the British and brought to Coimbatore.

Chengelpet became a hotbed of secret gatherings and revolutionary activities in the early period of the outbreak of the Revolt. Sultan Bakhsh went from Madras to Chengelpet in July 1857 to help organise the anti-British uprising there in cooperation with his local associates, Aruanagiry and Krishna, two leaders who were already leading a revolt in the area.

On July 31, an uprising took place in the Chengelpet area. The movement started spreading. On August 8, 1857, the Magistrate of Chengelpet informed the Government of Madras about this serious insurgency.

1857 in Madras And Malabar

(Excerpted from ‘Impact Of The Revolt Of 1857 In South India’, Shumais U, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 77 (2016), pp. 410-417)

Hindu and Muslim religious leaders also played important role in the revolt in the Madras Presidency. Gulam Ghose and Sheikh Mannu arrested from Madras city were sentenced to transportation, Sheikh Ibrahim from Thanjavur in March 1858, three Bengali fakirs, Narasimha Das, Damodar Das, and Nirguna Das in August 1857, Baldev Rao from Salem in October 1857, Mulbagu Swami arrested near Coimbatore were some of the religious leaders arrested from different parts of Madras Presidency in connection with the revolt.

K N Panikar argues the Mappilas of Malabar resisted against the landlords and British through out the colonial period and the main reason was agrarian greivences and the religion played as inspiration for oppressed Mappila peasantry. Eight Mappilas were arrested at Ponmalla Village in Ernad Taluk for singing a ballad praising the martyrs of 1843 outbreak and calling for the overthrow of British rule in India.

In September 1857 at Thalassery or Tellichery, another Mappila named Vanji Kadavath Kunji Mayan was arrested for giving a speech on the revolt in North India and the scarcity of rice in Malabar. Kunji Mayan died of diarrhoea at a Trichinopoly Jail hospital.

The colonial rulers in the Malabar used laws like the ‘Moplah Outrages Act’ or ‘Moplah War Knifes Act’ of 1854 to racially profile the Mappila community as a particularly criminal and dangerous one. They tried to show that these Mappila rebels were not really political rebels at all, but were ‘fanatics’ or madmen due to their community background.