BHOJPUR

I. Mathila (Dumraon block)

THIS block is dominated and virtually ruled by the Rajput landlords. Though individual landlords do not possess more than 125 bighas of land in this area, they are, nevertheless, quite prosperous (and, of course, arrogant), thanks to adequate irrigation facilities and a high degree of fertility of land. On the other side are the harijans (mainly Dusadhs and Chamars) — many of them are still bonded labourers facing medieval atrocities and oppression in the hands of the landlords. In between these two camps, there are middle peasants and other middle strata (mainly Yadavas and Muslims).

After the All-India Party Conference in 1979, efforts began to organise mass movements in this block. At first in the village of Khewali, a village committee was formed and it started functioning in a semi-underground manner. The overwhelming majority of the members of the committee came from poor and middle peasants. Uniting and organising the people against landlords, resolving contradictions among the people, and organising them against theft and dacoity — such were the main functions of this village committee. The committee used to conduct political propaganda over 10 to 12 neighbouring villages. Soon village committees were formed in other nearby villages, too, and Mathila was one of them.

But like all other places, village committees in this area, too, did not find the going smooth. Particularly the police started creating all sorts of obstacles in the name of maintaining ‘law and order’. In response, the people of many villages rose in militant resistance against police interference. This resistance was so militant that the police did not dare enter the villages in small numbers. Once a police party headed by a sub-inspector tried to enter a house in Khewali village. The village womenfolk immediately encircled the police party, bashed them up and forced them to retreat.

At this juncture it was realised that the mass upsurge must be combined with movements on economic issues. Members of the Khewali village committee and cadres of other villages jointly issued a leaflet in which the following demands were placed on five specified landlords :

(i) withdraw the illegal and unauthorised occupation of a middle peasant’s land (this applied to one particular landlord),

(ii) withdraw all pending cases against peasants, and

(iii) increase wages. It was announced that whoever would not concede the demands would be socially boycotted. The land under the said illegal occupation was seized by the committee and restored to the concerned middle peasant. Side by side, agrarian labourers stopped working on the fields of those five landlords. Ultimately, four landlords conceded the demands, but the other, Jitendra Tiwari of Koran Saraiyan refused to compromise, and instead sought help from the police.

But just as the police unleashed a reign of repression, the struggle, too, turned against police repression. In one instance, armed policemen were taking away in a tractor the goods they had confiscated by raiding the house of a peasant cadre. But although they could break through the resistance put up by the people of that very village, soon on their way they were encircled by thousands of masses rushing out from neighbouring villages. With women lying down in front of the tractor and the swelling mob continuing to get more and more furious, the police could not proceed an inch. The gherao continued from morning till evening, when at last the DSP arrived on the scene and a peasant leader, too, reached the spot. The gherao was then lifted and the policemen allowed to leave, but only without the goods they had confiscated.

After this heroic resistance, the police further intensified their repression. Three of our comrades — Jeevan (Mukhtar Ahmed, member of Bhojpur Regional Party Committee), Vikas (Jai Govind, ex-worker in Rohtas Industries, Dalmianagar, and Party organiser in that area), and Narsingh (poor peasant, member of armed squad) — embraced martyrdom. Members of the village committee were all arrested. In face of such a heavy loss and repression, the mass upsurge temporarily subsided.

But the impact of the upsurge was widespread. And in its wake there developed a solid base over 30-40 villages in the area. Village committees were formed in almost all these villages. The poor and middle peasants as well as a section of rich peasants closely associated themselves with the movement. Soon after the Khewali struggle, Mathila came to the fore. New cadres emerged in the process of the movement and they embarked on an intensive propaganda. To ensure that the propaganda soon took on an agitational shape, the issue of 1,400 bighas of vested land was made its focal point. The village committee organised the landless and poor peasants and a memorandum was submitted to the administrative officials. In the mean time, two big ponds (of 52 bighas each) that were so far under the occupation of the landlords, were captured by the peasants. With their armed goons, landlords then attacked some peasants while the latter were fishing in the ponds. But they were soon chased away by a mass of 250 peasants. The masses also managed to catch hold of one of those goons, who was released only after 15 days after being issued a stern warning.

One of the landlords, Jagdish Singh, tried to mobilise the Rajput peasants against the struggling poor and prepared a blueprint for murdering peasant cadres. But thanks to correct and timely initiative on the part of the committee, middle peasants as well as a section of rich peasants of the Rajput caste came over to the side of the committee and Brahmin peasants were neutralised. Next the village committee mobilised poor and lower-middle peasants to capture a plot of vested land. The first bid was successful and as a mark of their control the peasants posted a red flag on the land. But the flag was soon uprooted by landlords and their armed goons and the peasants were threatened with dire consequences. The peasants were however not to be cowed down, and the very next day, accompanied by their armed squad, they made a bid to recapture the land. Fire was exchanged between the two sides, but ultimately the landlords were forced to beat a retreat. Peasants caught hold of four goons and gave them a thorough bashing. Out of panick, some landlords fled the village while others began to talk in terms of a compromise. This incident generated a renewed upsurge. A meeting of about 2,500 peasants was organised on the question of land, and a procession was taken out. Social boycott was enforced against two landlords. Peasant cadres widely propagated the agrarian programme of the Kisan Sabha and enlisted the support of middle peasants as well as a section of rich peasants of all castes. But as far as the landlords were concerned, they again fell back on the police and the administration. Many times cadres were sought to be arrested, but all the arrest bids were foiled by militant resistance on the part of the organised peasantry.

However, certain anarchist elements also managed to penetrate into the peasant organisation. One of them, an aggressive youth, even came to exercise a strong influence on the organisation, including the local peasant leader, thanks to his display of great militancy. While the land struggle was getting intensified, these elements arrested a person, a suspected police agent, who was allegedly responsible for the murder of our three comrades, and demanded that the armed unit execute him. The unit did not oblige them and instead advised them to free that person and concentrate on the land struggle, promising full assistance as would be demanded by the struggle. These elements, however, condemned the commander of the unit as a coward and with the tacit approval of the local peasant leader, they went on to annihilate that person.

As apprehended by the unit, this anihilation brought a temporary setback to the cause of the land struggle. However, the peasant organisation gradually regained the initiative and formed an eleven-member land committee comprising mainly lower-middle and poor peasants from different castes and communities. Certain women members were also there in the committee. Prior to distribution, the committee conducted widespread propaganda about the seizure of the plot of vested land and about the mode of distribution to be followed. The police again intervened and the officials sought to divide the people through a parallel allotment of parchas. But under the leadership of the Kisan Sabha, peasants rejected the officials’ orders and demanded that parchas be issued according to the decisions of the land committee. This enraged the officials and they filed cases against many peasants accusing them of taking the law into their own hands. To defeat this conspiracy of dividing the peasants, a massive demonstration was staged in front of the SDO Court and the officials were forced to withdraw the cases.

After conducting extensive discussion, it was decided that land (amounting to a total of 150 bighas) would be equally distributed on individual basis among all those who had participated in the struggle. Subsequently, it was decided that care would be taken to accommodate also those persons who, for some reason or other, were not in a position to physically take part in the struggle. The distribution took place under two heads — house sites and cultivation. Nearly 20 bighas of land were distributed for the purpose of cultivation, and the rest for housing. The land policy stipulated that

(i) land would be distributed mainly among poor peasants, and middle peasants would get land only for building houses or barn;

(ii) if the official allotment were to go against the allotment made by the committee, peasants would abide by the latter;

(iii) no allottee would be allowed to sell the allotted plot of land, and if an allottee dies without an heir, the concerned plot of land would return to the possession of the committee;

(iv) a portion of land would be earmarked for collective cultivation and its produce would go to the fund of the peasant organisation; and

(v) a cooperative system would be developed which would deal with marketing as well, so as to prevent distress sale by the peasants, and the income from the two tanks under the possession of the peasant organisation would be utilised for the development of agriculture.

The trouble within the organisation was, however, far from over. Instead of changing his ways, that youth had only intensified his anarchist activities. It was also revealed that he had clandestine links with the Rajput gentry. At this stage he was expelled from the organisation. Following this, he unleashed a slander campaign against the local peasant leader, and raising the bogey of ‘undemocratic expulsion’, he virtually formed a parallel group in the village. The masses seem to be more or less equally divided between these two parallel forces. In the final analysis, this rather unexpected division in the ranks of the people seems to reflect the dissatisfaction of a large number of people with the land policy and its implementation. Particularly, the pronounced pro-participant bias in the distribution of land does not seem to have gone down well with the masses. And with the masses thus divided, none of the recipients of the distributed land has so far dared to start cultivation on the distributed land. The administration has taken the fullest advantage of this impasse, once again it has intervened in a big way to spread fresh illusions. On the one hand, encroachment notices have been served on the peasants who are currently occupying the vested land, and on the other hand, these very peasants have been allotted vested land in a neighbouring village.

The struggle in Mathila is thus clearly at the crossroads. The Party is reviewing the situation and efforts are on to break through the present impasse.

The wave, of this organised movement for land seizure has already spread to six nearby villages and advanced cadres from Mathila are fanning out to spread the message of their struggle and to organise the peasants

II. Sahar

In its second phase, the movement in this block began in 1978. The Party forces started fresh efforts to rejuvenate the movement by waging mass struggles and developing mass organisations. An important development in this regard was the demonstration of 3,000 people at Arrah demanding the release of Girija Ram, an advanced peasant cadre as well as a member of an armed unit. This was the first ever mass demonstration led by us in Bhojpur district. Some middle peasants and PCC men, too, participated in it. By the end of 1979, a Jan Kalyan Samiti was formed, and during the 1980 famine, the Samiti organised a demonstration of at least 7,000 people at Sahar block office demanding declaration of Sahar as a drought-affected area and proper distribution of adequate relief. The activities of the Samiti frightened the landlords and they planned to set fire to one harijan tola. The Samiti immediately rose in action, exposed this conspiracy through mass meetings in several villages and staged a 5,000-strong demonstration before the block office on this and other economic issues.

In the face of landlords’ armed attacks and the police letting loose a veritable reign of terror, peasants’ armed forces felt that they badly needed more modern arms. With this end in view, our armed unit in the area attacked Fatehpur police camp and in a successful guerilla operation, snatched 7 rifles and 280 cartridges.

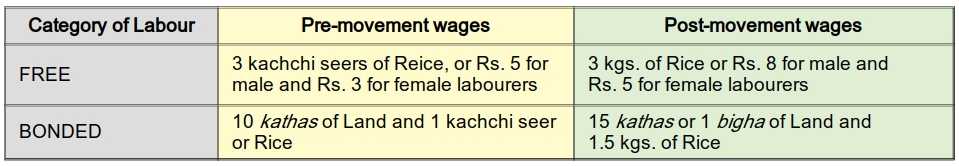

Meanwhile, the Korodihri village committee was striving to mobilise the agrarian labourers and poor peasants of some 5 to 10 neighbouring villages in a wage struggle against the landlords of Kharaon. (Sahar is dominated by Bhumihar and Rajput landlords possessing on an average 100 to 150 bighas of land.) A struggle committee was formed and demands raised. The landlords reacted by mobilising the entire Bhumihar community against hiring agricultural labourers. Instead they were encouraged to lease out land to the middle peasants. The committee then launched a counter-campaign to dissuade the middle peasants from taking land in lease, and the campaign proved quite successful. Enraged, the landlords decided to plough all their land by themselves. But they failed miserably in this venture and out of desperation, the ringleaders of their camp then planned to finish off the leaders of the movement. To start with they burnt down several houses. Initially, the masses got somewhat frightened. But the peasant cadres made all efforts to keep up the morale of the masses. They informed the police about the atrocities of the landlords. The Korodihri village committee imposed fines on, and collected grains and levy in kind from, rich peasants to support agrarian labourer/poor peasant families on strike. One mukhiya was punished by death for implicating peasant cadres in false cases. At this all landlords got panicky and expressed their desire to work out a compromise. Accordingly, negotiations were conducted in the presence of the officer-in-charge of Sahar police station and the BDO of Sahar leading to an increase in wages. This successful strike inspired the labourers of some 30 nearby villages. They too started planning a wage movement, but the plan did not have to be implemented, for, seeing no way out, landlords increased wages of their own accord. The following table shows the extent of wage-rise achieved through this struggle :

These achievements greatly boosted up the morale of labouring peasants in the entire area and gave a tremendous fillip to their struggles. At some places, the peasants also captured plots of land ranging from 30 to 125 bighas which are being collectively used for housing and cultivation purposes.

On the other hand, landlords and the police also mounted fresh attacks on this fresh eruption of peasant unrest. Raids were conducted in almost all the villages, but in most of the cases they did not go without resistance. Consider the case of Bahuara for example. The police had come to arrest one peasant cadre without any warrant. No sooner had this news spread than thousands of peasants from neighbouring villages rushed to Bahuara and encircled the police party. The latter began to tremble in fear, begged for mercy and finally took to their heels.

Apart from such direct resistance, the Kisan Sabha (the Jan Kalyan Samiti had later merged with the Kisan Sabha) also organised protests on the plane of political propaganda. On the day on which the first demonstration was to be staged, the administration suspended all traffic and closed all the ways. But defying all these odds, a total of 250 people turned up in the demonstration, and the police resorted to lathicharge to disrupt it. The Kisan Sabha replied with another demonstration just after two months. This time despite heavy police bandobast no less than 7,000 demonstrators turned up and gheraoed the police station. Seeing the militant mood of the masses, the SP was forced to beg for mercy, but while the demonstrators were returning the police unashamedly lathicharged them.

Police atrocities are going on, so is the movement of the peasants. In village Kharaon, peasants have captured 30 bighas of vested land on the bank of the river and the same has been distributed among them through a committee. Efforts are going on to capture vested land in some other places as well.