PATNA

I. Lahsuna-Sikandarpur (Masaurhi PS)

PARTY work was reorganised in Sikandarpur village in 1979 with the harijans (mainly Musahars and Beldars) offering a strong base. A village committee was formed by some vanguard elements including two progressive-minded individuals from the Kurmi caste. At that time the committee used to conduct all its activities in legal form. It used to maintain its register and inform the block administration about all its programmes and plannings. Solving disputes among the peasants, repairing ahars and ponds for irrigation purposes, making arrangements for night-watch against theft and dacoity, seizing vested and waste land and distributing such plots of land among the poor, opposing all acts of social discrimination and oppression committed by the landlords — such were the main functions of the village committee. It used to hold its meetings openly in the presence of the majority of the villagers. Armed with traditional weapons, village defence squads used to guard these meetings. These activities made the village committee very popular not only in Sikandarpur but also in a number of nearby villages like Lahsuna, Gurpatichak, Sukthia, Bansidih etc. where too it helped the rural poor get organised. It stood as a great hurdle in the way of the hitherto unquestioned arbitrary rule of the landlords in all these areas. The first confrontation took place with a landlord named Jeolal Singh who had a large plot of vested land under his illegal occupation and was in the habit of beating and abusing the poor. The broad masses of peasants rose against him, and ultimately his uncle surrendered before the people, and expressed his readiness to hand over the plot in question to the agrarian labourers.

Soon the peasants of Lahsuna also formed a village committee, and it began to assert itself much in the same fashion as its counterpart in Sikandarpur. Here, one progressive individual from the Kurmis joined the movement as a cadre.

The landlords were, however, not sitting idle. Instigated by Mahendra Singh, a notorious landlord of village Amat, the Kurmi landlords started ganging up against the ‘Naxalites’. In April 1980 they set fire to the Musahar tola of Sikandarpur village. And just as the peasants of Lahsuna had earlier taken the cue from their brethren in Sikandarpur, now the landlords of Lahsuna also sought to follow the footsteps of their Sikandarpur counterparts. But here in Lahsuna the harijan masses opened fire on the attackers and successfully checked their advance. The next day agrarian labourers went on strike which lasted for 20 days. During this hartal, many incidents of crop-seizure took place, levies were collected and some firearms were purchased. In 1981, 300 people jointly captured an ahar and a pond in the village (which were so far under the occupation of two major landlords, Chhotan Singh and Bandhu Singh) and proclaimed the village committee's control over them. By this time, the Party organisation had asserted itself as the main force in the village. Certain Kurmi peasants had also expressed their desire to join the Party, but they were refused admission.

Strike broke out again during the season of paddy-sowing in 1981. Barring two landlords, Sahdeo Singh and Bandhu Singh, all others agreed to pay higher wages. Consequently, for two years, nobody went to work in the fields of these two persons.

It was in these circumstances that the Kishori Singh incident took place. This landlord, Raj Kishori Singh, had raped a village woman. In a villagers’ meeting it was then decided that he should be punished publicly. Accordingly, the village committee instructed the chowkidar to summon him and a public meeting was also convened. But somehow Kishori Singh had already come to know about this decision and had fled his house. Meanwhile Bandhu Singh had informed the police and soon a police party arrived in the village. And in an obvious attempt to save Kishori Singh from the wrath of the people, they arrested both him and the woman. Hearing this news, some 500 people immediately gheraoed the police party and snatched Kishori Singh away from their custody. It was decided that he should be executed and the decision was carried out forthwith. The next day a group of 150 armed policemen came to the village, beat up the villagers, ransacked their houses and arrested 21 villagers. But soon a mass of five to six thousand people gathered there and chased the police. But by the time they reached the railway station the police party had already left for Patna. Unable to get hold of the policemen, the furious mob attacked the station, ransacked it and pelted stones at the nearby police camp. Peasant leaders had a tough time pacifying the angry masses and bringing them back to the village.

After this incident, all the landlords of that village and of surrounding villages fled to Patna. In villages like Ghorahuan, Tandpar, Barah, Bela, Bagichapar, Sukthia, Sikandarpur, Niyamatpur and others, the crops and grains of Kurmi landowners were seized at random. A virtual “people’s raj” had been proclaimed, and this situation continued for about 5 months.

Afterwards police camps were set up in each and every village and with the active connivance of the police, the Bhoomi Sena entered the scene. The later years, often marked by armed clashes between the Bhoomi Sena and the people’s armed forces, are also full of instances of heroic struggles of the peasantry, but details are beyond the scope of the present collection.

II. Narhi-Pirhi (Bikram PS)

Land movement : During 1981-85, struggles for capturing vested land, ahars, river banks, ponds, orchards etc. were launched in a number of villages in this area like Narma, Pirahi, G. I. Dih, Jamui, Bharatpura, Lala Bhatsara, Rakasia, Kalyanpur, Narahi, Sabajpur, Soriama, Gorkhari, Arap and others.

In Narma village, some 1,000 peasants belonging to different castes (except the Bhumihars), under the leadership of the Party organisation, captured 60 bighas of vested land, including two ponds (of 12 bighas each) and an orchard,, that were under the illegal occupation of Bhumihar landlords. But the matter is not settled as yet as the landlords continue to put up a united resistance, and the struggle is still on.

In G. I. Dih and Bharatpura, peasants captured two ponds (one of 22 bighas and the other 20 bighas) which were hither-to under the control of the block office. Yet another pond (of 12 bighas) was captured in Pirahi village, and in Narahi, peasants established their control over a one-mile stretch of river bank in addition to five bighas of vested land and one ahar. Similar actions took place in other villages, too.

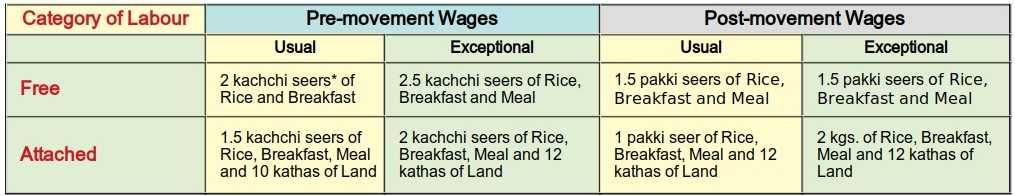

Wage movement : There are 32 panchayats and 128 villages in Bikram block. Of these, almost all the panchayats and more than half of the villages (72, to be specific) were affected by wage movement. In 38 villages, the movement was launched under the direct leadership of the Kisan Sabha, in another 11 villages it broke out spontaneously, in yet another 5 villages some other organisations led the movement while in the remaining 18 villages landlords increased wages without any direct movement. The increases in wages have been as follows :

* 1 kachchi seer = l/2 pakki (standard) seer

Resistance movement: The first mass organisation built up by our Party in this area was a youth organisation (formed in January 1980). And this very first effort evoked an atrocious response from the landlords, particularly from one Chalitar Yadav of Narahi village who had an illegal holding of 105 bighas. Later these village youths took initiative in forming a broad-based mass organisation, Jan Kalyan Samiti, and a few other organisations, which attracted the ranks of other political parties like the CPI, CPI(M), Janata Party and the Shoshit Samaj Dal. The Jan Kalyan Samiti staged its first demonstration at Bikram block on 30 September, 1980, demanding mainly the seizure of licensed guns and rifles of the landlords. And by January 1981, it had already grown strong enough to take out a 5,000 strong procession.

With the formation of the Kisan Sabha, all these earlier mass organisations merged with it. The branch organisation of the Kisan Sabha undertook extensive propaganda through village-to-village campaigns, panchayat level meetings, group meetings etc. In course of this propaganda and organisational work, it had to face many an attack from the landlords and the police. On September 24, 1981, the Kisan Sabha organised a militant demonstration and mass meeting against the repressive raj of the landlord-police-goonda combine. While the meeting was in progress, the police arrested two persons. Soon thousands of masses were on their way to the police station. Panicked, the policemen fled away and the infuriated masses then entered the police station, broke open the hajat (lock-up) and freed the two arrested persons. Women played a frontal role in this struggle.

After this incident the police arrested the secretary of the block committee of the Kisan Sabha, Rajeswar Ram, on 12 October, 1981. But again a mass of 4,000 peasants gheraoed the police station and got him released.

Soon after these incidents, in an obvious attempt to create terror in the area, landlords, led by the Congress (I), BJP, CPI, and some notorious Bhoomi Sena men, took out an armed procession with provocative slogans. Side by side, the police too intensified its attack. On 30 October, 1981, more than 100 armed police-men raided Narahi village, ran-sacked many houses, injured many villagers and arrested one student. The same police party then enacted a repeat performance of this brutal drama in Pirahi village. Here they shot dead Surendra Mahato, and while returning they killed Chandravati, a newly married girl of 15, when she was resisting the arrest of her cousin.

But these brutal repressive measures could not crush the revolutionary morale of the masses. In April 1982, hearing the news of the arrest of a person, thousands of peasants ran up to the police station, ransacked it, smashed the jeep and successfully freed the arrested person.